Collie eye anomaly (CEA) is an inherited syndrome of eye problems that can cause vision defects. The disease occurs in both eyes, but each eye may be affected differently. The dogs who are destined to have the syndrome are born with the inherited DNA mutation, although the abnormalities may or may not be present at birth, so technically it is not a birth defect. Symptoms of CEA, such as retinal folds, can appear after birth at a certain age and then disappear as the dog ages. Some retinal detachments can be progressive and worsen over time, so it can be a progressive disease.

About 50 years ago, veterinarians estimated that about 90 percent of collies carry the DNA mutation although not all those dogs have the syndrome itself. Lowering that percentage has been difficult because CEA affected such a large percentage of the breed. Thanks to eye examinations and selective breeding, the number of affected dogs has decreased significantly.

The syndrome has no cure, although there are some treatments for some of the eye problems, such as surgery for progressive retinal detachments if they worsen over time. Generally speaking, most dogs with CEA have abnormal vision and their vision is affected by choroidal hypoplasia and colobomas (see below) in addition to the retinal detachments.

Affected dog breeds generally include collies, Australian shepherds, border collies, Shetland sheepdogs, and the Lancashire heeler. Eye defects seen in the syndrome have been seen in atypical breeds and mixed breeds with collie-type heritage as well.

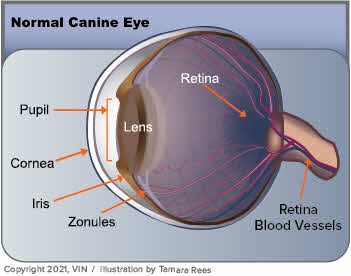

The problem in CEA is that an area of the retina (the nerve layer of the eye with rods and cones) and/or the choroid (the choroid is the blood vessel layer under the retina) does not develop the way it should because of DNA mutations. The damage to an individual’s vision depends on the severity of the syndrome. Many dogs are carriers of the DNA mutation but do not have the disease, while other dogs are affected and can have various eye problems as a result. It is possible for a retina to detach early or later in life, causing blindness in that eye.

Typically, CEA is diagnosed during a screening by a veterinary ophthalmologist who looks at the front of the eye and the fundus (back of the eye) when the dog’s pupils are dilated.

Before Breeding

The disease is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. To have this type of disorder, the dog inherits two CEA mutated genes, one from each parent. The dogs who have only one mutated gene for CEA from one parent do not have the disease and are called carriers. If a carrier is mated to a carrier, then 25 percent of the puppies will have the disease with two copies of the mutation, 50 percent will be carriers with one copy of the mutation, and 25 percent will be clear with no mutations. If a carrier is mated to a clear, then 50 percent of the offspring will be clear, and 50 percent will be carriers.

That’s why dogs with CEA or carriers of the CEA mutation should not be bred to each other

Breeders of dog breeds affected by CEA should have their dogs screened for CEA before breeding individual dogs. The genetic test for CEA can determine all three genetic states of a normal carrier, and affected with 90-95% accuracy. Even puppies can have genetic tests as long as they are large enough for your veterinarian to safely take a teaspoon of blood to send in for testing.

It is ideal to breed clinically normal dogs to each other, which can be difficult if there are not many clinically normal dogs in the geographic area. Unfortunately, dogs that appear normal may still be carriers for the CEA mutation, and breeding two carrier dogs to each other can still run the risk of producing 25% affected puppies and 50% carrier puppies. That means that even parent dogs with no signs of the CEA disease can produce severely affected puppies with blindness or ongoing eye problems. Nonetheless, selective breeding is helping to reduce the number of cases worldwide.

Puppies can be checked by a veterinary ophthalmologist at 5-6 weeks old, preferably before 12 weeks, and their pupils must be dilated for this examination. Responsible breeders should conduct genetic testing on the parents and eye exams on the puppies before 12 weeks of age to determine which dogs should not be bred or should be bred with care to another tested dog.

Specific Possibilities

The choroid, a blood vessel layer underneath the retina, can suffer from an abnormality in development referred to as choroidal hypoplasia. It is the most common problem found in CEA and occurs when the blood vessels do not develop under the retina so the retina cannot be viable or functional without a nutrient supply. The areas of choroidal hypoplasia cause blind spots in vision. Retinal folds can disappear with age so they may not be seen in the eye exam of a dog over 12 weeks of age and an eye exam just before 12 weeks of age is ideal.

The eye symptoms can be difficult to see without extensive training in veterinary ophthalmology and specialized eye exam equipment.

Sometimes, a separation will occur between the retina and the choroid causing a retinal detachment. The detached part might be just a small area of the retina or all of it. Complete retinal detachment results in blindness in the affected eye. Retinal detachment can be seen at any age. If a retinal detachment occurs in and blinds only one eye, dogs usually retain some vision from their other eye. Retinal detachment can cause vision loss but not pain or can cause recurrent bleeding in the eye. The worst possible outcome is recurrent bleeding in the eye that leads to glaucoma, blindness, and pain that requires surgery to make the dog comfortable.

A coloboma is a focal cupping or bulging in the eyeball, often near the optic disc. Severe cases of these can be associated with blindness or retinal detachments.

Retinal folds occur when the retina is too large for the eye and creates folds inside it. It is commonly associated with CEA. These folds sometimes resolve with age.

Vascular disease can cause a defect in the eye vessels that are responsible for the blood supply. These may be malformed, undersized, or might not even be there.

A diagnosis of CEA can be frightening but remember that vision is not always lost – at least not all of it – and procedures are available to lessen the impact of some of the painful issues. Preventing CEA is best done through screening eye exams and DNA testing in breeding dogs. Once the eyes are not formed properly, no cure is possible.