The EPA has been at odds with Reckitt Benckiser (the makers of d-CON) since 1999 when they began seriously scrutinizing the risks of rat poison products to pets, children, and wildlife. At last, Reckitt Benckiser has aggreed to comply with the EPA directives. This means that second-generation rat poisons (which kill rats in one feeding) will be banned from residential use and that rat poisons for residential use must be secured within bait stations (not in open trays). The traditional d-CON products have not been manufactured since December 2014 and have not been distributed since March 15, 2015. Bromethalin-based rat poisons have since captured the residential market. Commercial exterminators may still use the anticoagulant rodenticides discussed here.

Mankind and the rat have been in conflict for thousands of years. Rats spread disease, eat our crops, leave droppings and make nests in our storage areas, and infest our homes. Rodent removal services are an important part of pest extermination even in this century. Rat poison can be obtained in most hardware stores, grocery stores, and even for free from city agencies in some areas. While you may want to get rid of rats, you certainly do not want to pose a hazard to the children or pets of the family.

Research continues to create a product that fits this bill but in the meantime be aware of the signs of rat poisoning, particularly if your pet travels with you to places outside the home where bait may be left out.

There are several types of rodenticides available. The traditional products are called anticoagulant rodenticides and are discussed here. If you intend to use a rodenticide, we encourage you to choose this type over others as there is a readily available antidote for the anticoagulant rodenticides. Other rodenticides are more toxic and no antidote is available. You should know what product, if any, you use at home. Common anticoagulant rodenticides are: brodifacoum, dopaquinone, warfarin, bromadiolone, and others.

Most of these products include green dyes for a characteristic appearance; however, dogs and cats have poor color vision and to them these pellets may look like kibbled pet food.

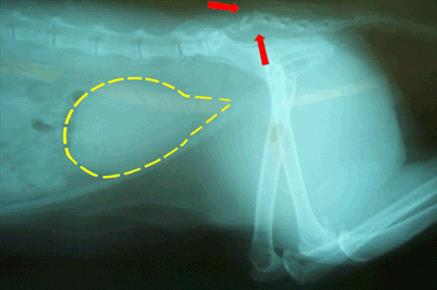

Anticoagulant rodenticides do not produce signs of poisoning for several days after the toxic dose has been consumed. Anticoagulant rodenticides cause internal bleeding. A poisoning victim will show weakness and pallor but bleeding will likely not be obvious externally.

Symptoms

Most of the time external bleeding is not obvious and you only notice the pet is weak and/or cold. If you look at the gums, they are pale. Sometimes bloody urine or stool is evident or nose bleeds may be seen. Signs of bleeding in more than one body location are a good hint that there is a problem with blood coagulation and appropriate testing and treatment can be started.

How Does Rat Poison Work?

You would expect the signs of a poisoning to be evident quickly but anticoagulant rat poisoning signs require at least 5 days to show up. Furthermore, unlike most poisons where treatment involves managing symptoms until the poison is out of the system, there is a true antidote for anticoagulant rat poison and it is actually a vitamin. How can this be? To understand what these poisons do, it is necessary to have some understanding of how blood clots.

A blood vessel is sort of like a pipe carrying rapidly flowing blood along its path. The pipe is lined by smooth flat cells called endothelial cells that facilitate the smooth flow of blood. If the pipe breaks, the structure of the pipe below the lining is exposed to the flowing blood inside.

From there the sequence of events is as follows:

- The blood vessel automatically constricts and spasms. This restricts the blood flowing to the damaged area and helps minimize blood loss.

- The exposed pipe attracts circulating platelets, cloud-like cells that circulate ready to assist in clotting should the need arise. Platelets clump together over the tear in the blood vessel, forming a plug within the first five minutes of the injury. This is all a good thing but the platelets will not stay in place unless a substance called fibrin can be made to bind them.

- Generating fibrin is complicated and beyond the scope of this article, but a cascade of activating proteins is needed to make the tiny protein threads (fibrin) that bind the platelets and makes a permanent platelet plug on the wound. Four of the proteins involved are called serine proteases, and these are the factors relevant to anticoagulant rat poisoning. These four factors must be able to work or there will be no fibrin, the platelets will not clump properly, and bleeding will continue without clotting.

About those Four Clotting Factors

The four clotting factor proteins are also called the K-factors because they depend on vitamin K for activation. After the clotting situation is under control, the used Vitamin K is recycled in the liver so it will be ready for the next time bleeding needs to be stopped. Anticoagulant rat poisons interfere with Vitamin K recycling. It takes several days to deplete the Vitamin K but after that is used up, there is no more and bleeding cannot be stopped. That is why it takes some 5 days for symptoms to show up and how it is possible to reverse this poison by giving more Vitamin K.

As long as there is plenty of vitamin K, the serine proteases can be activated and clotting can proceed normally. The anticoagulant rodenticides abolish vitamin K recycling. This means that as soon as the body’s active vitamin K reserves are depleted there can be no meaningful blood clotting.

In cases of poisoning you would expect symptoms to be nearly immediate but in the case of anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning, it takes several days to deplete vitamin K. After that, even the smallest of jostles and traumas can lead to life-threatening bleeds.

Testing

Testing can be done using clotting tests called a PTT (partial thromboplastin time) and PT (prothrombin time). These tests evaluate the activity of the four K-factors. If both these tests are abnormal, there is an excellent chance that anticoagulant rat poison is in the patient’s system. The PT test in particular bears special mention as it tests the least stable of the K-factors called Factor VII. This means that the PT test becomes abnormal before the PTT test becomes abnormal. When it’s time to monitor a patient for recovery, the PT test must be normal in order to declare the poisoning resolved.

Another test called the PIVKA (Proteins Induced by Vitamin K Antagonism) test is more specific. The PIVKA test detects inactive serine proteases. An unusually high amount of inactive K-factors circulating indicates something is wrong with Vitamin K recycling.

Therapy

If the patient has only just ingested the poison, he or she may be made to vomit it up. Cathartics and adsorbents can be used to prevent the poison from entering the patient’s system. Still, it is best to use the antidote anyway. Certainly, if there is evidence that the patient is bleeding, the antidote obviously is required.

The antidote is simply vitamin K.

Vitamin K is generally started as an injection, and when the patient is stable, tablets are prescribed. The human formulation, available as a prescription drug at most drug stores, is a 5 mg tablet. The veterinary strength is a 25 mg tablet. Blood transfusions may be needed to stabilize a patient who has suffered significant blood loss.

There are different classes of anticoagulant rodenticides, and they remain in the body for several weeks. It is hard to know when to discontinue therapy, especially if the particular rodenticide is not known. After a couple of weeks of therapy, the medication is discontinued. Forty-eight hours later, a PT test is run. If there is still rodenticide in the patient’s system, the PT will be abnormal, but the patient will not yet have started to bleed. The results of the PT test will tell the veterinarian whether or not another couple of weeks of vitamin K are needed.

It is important to return for the recheck PT test on schedule. Waiting an extra day or two will allow internal bleeding to recur. There is no point in doing the PT test while the patient is still taking vitamin K. The test must be done 48 hours after discontinuing the medication.

When the PT test has returned to normal, it is safe to discontinue therapy.

Vitamin K1 Vs. Vitamin K2 Vs. Vitamin K3

There are three forms of vitamin K but only vitamin K1 is used therapeutically. Vitamin K1 is a natural form of vitamin K that is found in plants and absorbed nutritionally. Its more technical name is phylloquinone. Vitamin K2 (menaquinone) is also natural and is produced by the body’s intestinal bacteria but apparently not in amounts adequate for rescue from the anticoagulant rodenticides. Vitamin K3 (menadione) is a synthetic version that may be injected or taken orally. You may even see it available as a vitamin supplement tablet.

Within the body vitamin K1 and vitamin K3 are converted to vitamin K2. Vitamin K3 might seem like an inexpensive way to treat a pet with rat poisoning but unfortunately, K3 is sometimes toxic and can actually lead to red blood cell destruction. Inexpensive vitamin K3 pills on the drugstore shelf for over-the-counter sale are not acceptable antidotes. Vitamin K1 is used because it is absorbed early in the GI tract and concentrates directly in the liver, which is where the K-factors are activated.

It is only vitamin K1 that should be considered to be the antidote for anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning.

Other Rodenticides

While anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning is a life-threatening event, at least there is an antidote readily available. Other rodenticides are not as readily reversed. These rodenticides include:

- Quintox, Rat-B-Gone, Bromethalin (see an additional article)

- Strychnine, gopher bait

- Zinc phosphide, gopher bait

Pets Who Eat a Poisoned Rodent

We are commonly asked about the risk to a cat or dog who eats a rodent that has been poisoned with an anticoagulant rodenticide. The rodent might have already died or simply not have died yet given that several days are required to feel the effect of these poisons. The fact is that when you’re talking about the newer generation anticoagulant rat poisons, such as diphacinone, the risk is real. A greedy rat can eat enough poison to kill 20 rats before he starts to feel sick, and if this was a second generation rodenticide it will accumulate in the rat’s liver ready to poison the cat that eats the rat’s liver. Fortunately, second-generation rodenticides have been banned for residential use. First-generation rodenticides are no longer in the rat’s body after several hours, making pet poisoning less of a concern. Furthermore, most rats do not overindulge in poison. The usual patient for secondary poisoning is a pet or predator that depends heavily on rats for food (a barn cat, for example). There is some controversy over how often this actually happens, as most pets do not consume numerous rats.