Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Dogs and Cats

When squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) occurs in the mouth and throat, it’s called oral squamous cell carcinoma. In these oral cases, the lesion is usually located on the gums or tonsils. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common oral cancer in cats. In dogs, SCC is the second most common oral tumor.

The most common location of oral SCC in cats is on the base of the tongue on the underside. SCC may also come from the gingiva (gums), particularly along the maxillary (upper) teeth.

SCC on the gingiva expand and progress locally and are usually associated with destruction of the bone. SCC of the maxilla (upper jaw) often appears as a depressed, ulcerated area. The tumors on the tongue, mandible (lower jaw), and pharynx (throat) tend to be proliferative and raised.

SCC metastasizes (spreads) to the regional lymph nodes less than 10% of the time in dogs and 31% of the time in cats. Metastasis to the lungs occurs 3-36% of the time in dogs and 10% of the time in cats. SCC are typically very invasive and can become quite large, especially in cats.

SCC affects middle-aged to older cats (range 7-20 years). There is no increased likelihood based on breed or gender.

Signs

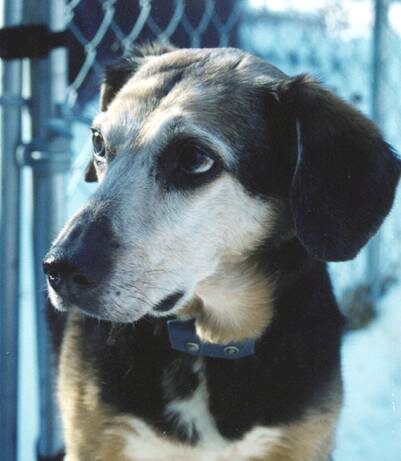

Signs can include drooling (with or without blood), difficulty eating, and halitosis (very bad breath). Depending on the tumor’s location, the pet can have trouble swallowing or may cough. If the mouth is too uncomfortable for the pet to eat normally, they will lose weight. As is true with many cancers, affected dogs and cats tend to be older animals.

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostics include radiographs (X-rays) of the local site, radiographs of the lungs to see if it has spread (metastasized) to other locations, CT scans, biomarker assessment (laboratory tests), and biopsies. Sometimes a fine needle aspirate will provide enough sample tissue for diagnosis. In a study of oral SCCs, biomarkers (such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen and Ki-67) were associated with higher-grade tumors and increased likelihood of spread.

Treatment

Treatment may involve surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, electromagnetic thermoablation, supportive therapy, or a combination of these depending on location, the amount of tissue involved, etc. Your primary veterinarian or veterinary oncologist will recommend treatment options specifically for your pet’s condition.

Surgery

If the tumor hasn’t spread, surgery is the preferred treatment. The entire tumor, including the extensions into underlying tissue and bone, will be removed. Often, part of the jawbone has to be removed. Surgery can provide a cure if the pet has clean margins (the tumor was completely removed). Dogs do quite well with partial jaws. It doesn’t typically alter the dog’s appearance as much as people might expect. Even if surgery isn’t curative, surgery can extend survival.

As for cats, following radical mandibulectomy (removal of the lower jaw) most can eat independently, but a few may require hand feeding. In cats, surgical excision, with or without partial removal of the tongue, may be considered for SCC of the tongue. When dealing with SCC of the pharynx (throat) or tonsils, the specialist may recommend removing as much of the mass as possible to make the cat more comfortable. This is palliative, but it’s not curative.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy can be used if surgery isn’t an option, or if surgery can’t completely remove the tumor.

In cats, radiation therapy is not very effective as the sole therapy for SCC because median survival times (MST) range from only a few weeks to months. In a report of combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy, the overall MST was 163 days, and cats with tumors of the tonsil or cheek had MST of 724 days. Radiation therapy has been used as palliative care for cats with nonresectable SCC.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy may be added to therapy, depending on the circumstances. Chemotherapy has some drawbacks, so your veterinarian or oncology specialist will have to determine if this treatment would be useful.

Electromagnetic Thermoablation

Electromagnetic thermoablation (hyperthermia, in which body tissue is exposed to high temperatures) may be used. This technique applies a high-frequency alternating electromagnetic field to heat alloy needles. The needles are placed into and surrounding the tumor to destroy the malignant tissue.

Supportive Therapy

Supportive therapy includes pain medications, acupuncture, feeding tubes to provide nutritional support, antibiotics for secondary infections, etc. A few cats with oral SCC have been treated with the medication zoledronate in an attempt to reduce bony destruction and pain. Pamidronate is also a medication option for cats. Your veterinarian will work with you to determine what therapies apply to your pet.

Monitoring

Frequent examinations are needed to watch for recurrence or progression. Periodic monitoring to watch for evidence of spreading disease, such as feeling the lymph nodes, lymph node aspiration, and chest X-rays are also indicated.

Prognosis

Prognosis For Dogs

The median survival time for dogs that have mandibular (lower jaw) SCC treated with surgery alone varies from 19-43 months, with a 1-year survival of 88-100%, a 2-year survival of 79%, and a 3-year survival of 58%.

The median survival time for maxillary (upper jaw) SCC that was treated with maxillectomy varies from 10-39 months. The local recurrence rate after mandibulectomy or maxillectomy is less than 10%.

Tumor-associated inflammation and invasion of the lymphatic system are indicators of a poorer prognosis. Overall survival times are lower with SCC of the tonsils. In one study, the median survival time was only 243 days, with a 1-year survival rate of 40% and a 2-year survival rate of 20%. The longest survival times occurred when surgery and chemotherapy were used together.

Prognosis For Cats

Overall prognosis is poor. One study of 21 cats treated with mandibulectomy reported a median survival time (MST) of 217 days, with 1 and 2-year survival of 43%. The local recurrence rate was 38%. Cats with rostral (nose/mouth) tumors had a longer MST of 911 days. When SCCs of all oral tissues are included, MST with no therapy is only 30-45 days. MST was 106 days following stereotactic radiotherapy for oral SCC of any location, with 38.5% of the cats showing a positive response. Most cats with this tumor type die of uncontrolled local disease. Another factor adversely affecting survival is that many cats with advanced SCC have metastatic disease (lymph node 31%, lungs 10%) at the time of diagnosis.