Calcium Phosphorus Balance in Dogs and Cats

In renal insufficiency, phosphorus is not anyone’s friend. The same phosphorus that has so many helpful roles in the body (from transferring biochemical energy to combining with calcium to form bone), turns against us in a condition called renal secondary hyperparathyroidism.

The short version is that the failing kidney is no longer good at getting rid of excess phosphorus and phosphorus levels in the blood begin to rise. The rise in phosphorus upsets the delicate balance between calcium and phosphorus and activates a regulatory hormonal cascade that attempts to re-establish control. Without healthy kidney tissue to play its role in this balance, the body is fighting a losing battle. Calcium is mobilized from bone to balance the phosphorus but in the end this only serves to demineralize and weaken the bones and cause calcium phosphate deposits to form in soft tissues. These mineral deposits are inflammatory and damaging.

The hormones that play roles in the regulation of calcium and phosphorus are parathyroid hormone and calcitriol (which most of us know as Vitamin D). The story co-stars a substance called Fibroblast Growth Factor 23. These three materials interact to maintain a normal and effective blood calcium level without allowing phosphorus levels to run away.

We’ll review the story of how this works.

Keeping Calcium Under Control

While our discussion of renal disease largely revolves around phosphorus, the importance of calcium cannot be underestimated. The movement of calcium ions is what allows our muscle fibers to contract, not just in our arms and legs but also in our hearts, and involuntary intestinal and blood vessel muscles as well. Calcium combined with phosphorus makes up bone; in fact, bone can be considered a storage depot for calcium when we need some in a pinch. The blood level of calcium is tightly regulated by hormones within a narrow range as too much calcium is as dangerous as too little.

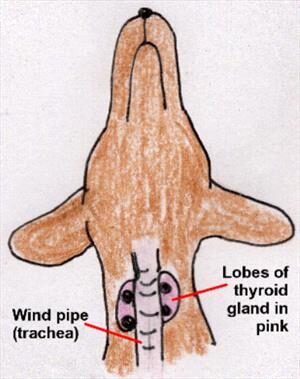

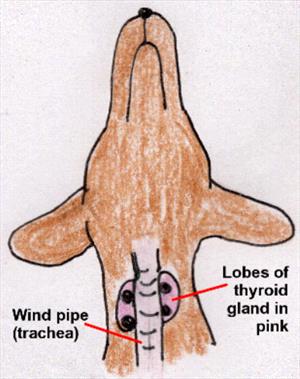

There are four tiny parathyroid glands around the thyroid gland in the throat area. These glands produce a biochemical called parathyroid hormone (often abbreviated PTH). PTH basically raises calcium and activates vitamin D, which further raises calcium. It sounds like calcium would just continue to rise out of control but there is a safeguard. When active vitamin D levels get to a certain point, they shut off PTH production. Calcium levels then drop down and between these two hormones, blood calcium is regulated within a healthy range.

Keeping Phosphorus Under Control

When it comes to phosphorus, PTH and calcitriol no longer work together. PTH signals the kidney to dump phosphorus while calcitriol signals the kidney to save it. In the normal body, the coordination of these hormones works out to keep calcium and phosphorus levels in balance, no matter what is happening with the blood calcium.

All this goes along swimmingly until the kidney is too damaged to respond to its hormonal signals or properly activate calcitriol.

Parathyroid hormone causes the kidney to dump phosphorus while vitamin D causes the kidney to save phosphorus.

What Happens in Kidney Failure?

In early kidney failure, the kidney becomes unable to get rid of phosphorus normally, and as a result phosphorus levels begin to rise. This activates a substance called Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (affectionately known as FGF-23) from the bones. FGF-23 encourages the kidney to dump more phosphorus and dampen the activation of vitamin D (remember that vitamin D tells the kidney to save phosphorus). As part of its mission to dampen vitamin D, FGF-23 also instructs the parathyroid glands to cut back on PTH. All this vitamin D suppression is all well and good and helps keep the phosphorus levels reasonable, but pretty soon FGF-23 has dampened both PTH and vitamin D so well that calcium levels begin to drop.

And this is where calcium-phosphorus Hell breaks loose.

At this point, kidney failure is no longer early. Dropping calcium levels supersede any FGF-23-mediated suppression of PTH and the parathyroid glands crank up PTH production to bring calcium levels back up. To meet the body’s demand for circulating calcium, the bones liberate their structural calcium to save the day, but unfortunately doing this also liberates more phosphorus. This leads to an even higher phosphorus level. Circulating phosphorus binds the circulating calcium creating crystals that deposit in the body’s soft tissues and generate inflammation. Bones are weakened and replaced with fibrous tissue. Calcium is depositing uselessly all over the place and the parathyroid glands must crank even harder to keep calcium levels livable. A metabolic disaster has occurred at this point.

Making matters worse are other effects of excess parathyroid levels. In high amounts, nerves cannot conduct electrical impulses properly. Patients become dazed and poorly responsive.

The goal is to keep the phosphorus level from getting out of control in the first place. If this is not possible, the goal is to get the phosphorus level back under control and keep it there.

Treatment

How do we Control Phosphorus Levels?

The goal phosphorus level defined by the International Renal Interest Society is between 2.5 and 4.6 mg/dl for earlier renal insufficiency stages and to keep phosphorus levels under 6 mg/dl for Stage Four (more advanced) patients.

Fluid Therapy

Often simply giving fluids under the skin at home provides enough extra circulation through the kidneys for the extra phosphorus to be excreted normally. Further treatment may not be needed. Hydrating a damaged kidney effectively maximizes the kidney’s remaining function, and this may be enough to control phosphorus.

Therapeutic Diet

It is important to remember that ultimately phosphorus balance is a matter of balancing phosphorus entering the body with phosphorus leaving the body. If the kidney is no longer effective at removing phosphorus, we can perhaps work on limiting the amount of phosphorus entering the body. The first step in doing this is with a therapeutic renal diet. These diets are designed to give the kidney less work to do, and that includes limiting phosphorus entering the GI tract. After one to two months on a phosphorus-restricted diet, blood tests will indicate whether or not additional phosphorus treatment is needed.

Phosphate Binders

These products are given with food to bind phosphorus in the food. The complex of phosphorus and phosphate binder cannot be absorbed into the body with the result being reduction of incoming phosphorus. If the pet will not eat food containing the binder, the binder can be given just before or just after the meal but the binder must be in the GI tract at the same time as the food or it will not work. There is no point in giving a binder to an animal that is not eating. Giving the binder before the meal can induce enough stress so that the pet will not eat so it is better to give the binder after the meal if the binder is not accepted mixed in the food.

There are a number of phosphate binders available and which one is selected will depend in part on the concurrent calcium situation. This means that the ionized calcium level (not the total calcium level) must be measured. Some binders also supplement calcium while others drop or have no influence on calcium. Some patients require more than one binder to get their phosphorus value low enough.

Calcitriol

You might think that calcitriol would not be helpful in this situation since it leads the kidney to retain phosphorus. The good news is that when small enough doses are given, calcitriol can still act as the off switch for parathyroid hormone without causing the kidney to retain phosphorus. The amounts needed for this beneficial effect are so small (they are measured in nanograms) that a compounding pharmacy is needed to custom-make the product at the proper dose.

- Calcitriol cannot be used in patients with elevated blood calcium levels.

- Calcitriol cannot be used in patients with phosphorus levels that are already abnormal. This is a preventive measure more than a treatment.

Renal secondary hyperparathyroidism and its associated high blood phosphate levels are one of the most common uremic toxin issues in treating kidney disease. Dedication is required to get phosphate binders into the pet along with food when the pet’s appetite is weak. Phosphate binders come in powders, liquids, capsules, compounded flavored chews, and other formats. Consider what approach is likely to work best for your pet but, remember, the binder only works with food.