Hypertrophic Osteodystrophy (HOD) in Dogs

Hypertrophic osteodystrophy is a developmental, auto-inflammatory disease of the bones that is usually first seen between 7 weeks and 8 months of age. In general, most cases will appear for the first time when the puppy is between 3 – 5 months of age. Relapses may occur until about 20 months of age.

HOD is most often seen in fast-growing puppies of large and giant breeds.

Some medium-sized breeds, such as the Australian cattle dog and pit bull may also develop HOD. The Weimaraner, in particular, appears to be predisposed to HOD.

Predisposed breeds include:

- Australian kelpie

- Boxer

- Bullmastiff

- Doberman pinscher

- German shepherd dog

- Giant breed dogs

- Great Dane

- Irish setter

- Irish wolfhound

- Kuvasz

- Labrador retriever

- Large breed dogs

- Rottweiler

- Saint Bernard

- Standard poodle

- Weimaraner

In HOD, blood flow decreases to a part of the bone next to the joint. This interrupts bone formation. The interruption means that bones don’t harden appropriately, nor do they grow as strong as those of a healthy puppy.

HOD can be very painful. Sometimes HOD is straightforward and responds quickly to treatment, but it can also be tricky to diagnose and treat.

HOD is somewhat similar to panosteitis (pano) in that it affects the growing leg bones of large- or giant-breed puppies. However, pano usually affects only one leg at a time, and is thought of as “growing pains.” HOD can affect more than one leg at the same time and is more painful than panosteitis. In addition, unlike pano, HOD can permanently damage the growth plates.

HOD doesn’t appear to be inherited, and at this time no one knows how puppies get it, although auto-immune diseases and dietary excesses can trigger it. However, because it is more common in some breeds if the puppy is being considered for breeding purposes, your veterinarian may recommend a thorough review of the pup’s relatives, to see how many of them have had HOD. If the puppy comes from a bloodline that has few cases, or the cases were mild and self-limiting, that may be better for breeding purposes than bloodlines that have had many cases, or have severe cases. (Every pup, of every breed, being purchased for breeding purposes should always have an extensive review of the relatives, to avoid known breed-related issues.)

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs depend on how mild or severe the HOD is. For mild cases, the puppy usually has a slight limp and appears to have pain in the affected bone. Puppies with more severe cases may have a decreased appetite and subsequent weight loss, fever, and depression. Unfortunately, these non-specific signs can happen with many diseases.

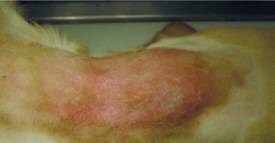

More specific signs of HOD include swollen, warm, and painful leg bones. The puppy may refuse to bear weight. If multiple limbs are affected, the puppy may prefer to remain lying down, be reluctant to get up, and be unwilling to walk.

And not just the legs may be involved. Some cases have swollen muzzles, excessive salivation, and pain when the dog tries to open his mouth; these cases may involve the jaw. Also, radiographs may show changes in the jaw, spine, ribs, shoulder, and eye socket bones.

Systemic signs can include:

- Fever ranging up to 106⁰F (a dog’s normal body temperature is 101-102.5⁰F)

- Lack of appetite

- Discharge from the eyes or nose

- Bumps on the skin, some with pus

- Diarrhea that can be bloody

- Inflamed vulva or vagina

- Increased respiratory sounds

At the very least, HOD dogs will have a fever, lameness, and typical HOD lesions showing on the radiographs. The more signs the puppy has, the more severe the case. (In severe cases, with multiple systems and organs affected, more aggressive treatment to suppress the immune system will be necessary.)

A complicating factor to remember is that, for the most part, HOD patients are very young puppies that do not have bodily reserves and can decline rapidly with fever and lack of appetite.

HOD can be a painful condition and typical treatment to control even significant pain may not work.

HOD generally comes in episodes that last a few weeks. Often the first episode lasts a week and it can be followed by a full and spontaneous remission.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made via physical exam (seeing obviously swollen soft tissue over the leg bones), radiographs, blood tests, etc.

Treatment

Your veterinarian will want to control the fever, lethargy, and bone pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often used for this. However, if the puppy develops gastrointestinal signs, the NSAIDs may have to be discontinued.

Some puppies may need immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids, usually prednisone. Some dogs may need to take them for a year, in which case the drug must be tapered off slowly, rather than simply stopped. Your veterinarian will recommend tapering only once the dog is free of pain and walks normally.

In some cases, narcotics may be necessary to control severe pain. These may have to be given by intravenous injection.

Some breed-specific studies have shown better responses to corticosteroids than to NSAIDs. In one study of 53 Weimaraners, 50 percent did not respond to NSAIDs. In another study of six related Weimaraners, NSAIDs had little effect and the dogs had to be switched to corticosteroids. A similar experience has been reported in affected Irish setters and Australian kelpies.

Your veterinarian may need to prescribe antibiotics for pneumonia or to prevent secondary infections resulting from immune systems that have been depressed by the corticosteroids. Antacids, such as famotidine, may be given while the dog is taking the corticosteroids. Some veterinarians may recommend probiotics when the GI tract is involved. Pain medications may be needed.

Other care may include fluid therapy, analgesics (e.g. tramadol, opiates), and rest or restricted activity. Even when the puppy starts feeling better, the veterinarian may still want exercise to be restricted until the bones have structurally recovered.

Vaccines should be avoided during an active HOD episode.

Monitoring and Prognosis

Mild cases of HOD may resolve on their own or with only supportive care. Watch for a possible return of any clinical signs once the dog has stopped/tapered the NSAIDs or prednisone because recurrences are common until the leg bone has finished growing. Dogs with affected litter mates are more likely to relapse. Complete recovery is expected once the leg is finished growing, but relapses (episodes of fever and malaise) have been reported in adult dogs. Most relapses in adult dogs respond to NSAIDs or corticosteroids.

Permanent limb deformities are rare. However, if they occur, surgery may help. Your veterinarian will use radiographs to determine if surgery is indicated.

Prevention

While it’s difficult to prevent a disease when you don’t know what causes it, some common sense can boost the chances that a puppy won’t get it. Large- or giant-breed puppies should not be given any mineral or vitamin supplements that aim to increase their growth rate and adult size. Slow and consistent growth is ideal for the puppy’s health because rapid growth can cause skeletal abnormalities. Puppies need a completely balanced diet. Puppies should be discouraged from doing jumping exercises until their growth plates have closed, which is at about a year of age. (Check with your veterinarian for an appropriate estimate of growth plate closure based on your puppy’s breed and growth.) Avoid housing puppies on hard surfaces, such as concrete. If floors are not carpeted, rugs may help so the puppies don’t slip as much.

Prognosis

Most cases of HOD are resolved with or without medical care. Unfortunately, sometimes HOD is so severe, painful, and uncontrolled by treatment that owners are forced to discuss the pet’s quality of life issues, resulting in euthanasia.