Kennel cough is an infectious bronchitis of dogs characterized by a harsh, hacking cough that most people describe as sounding like “something stuck in my dog’s throat.” This bronchitis may not last long and be mild enough not to need any treatment, or it may progress to life-threatening pneumonia depending on which infectious agents are involved and the patient’s immunological strength.

An uncomplicated kennel cough runs a week or two and entails frequent fits of coughing in a patient who otherwise feels active and normal. Uncomplicated cases do not involve fever or listlessness, just lots of coughing.

Numerous organisms (some of which may be prevented by vaccination) may be involved in a case of kennel cough; it would be unusual for only one agent to be involved.

Infections with the following organisms frequently occur concurrently to create a case of kennel cough:

- Bordetella bronchiseptica (bacteria)

- Parainfluenza virus

- Adenovirus type 2

- Canine distemper virus

- Canine influenza virus

- Canine herpesvirus (very young puppies)

- Mycoplasma canis (a single-cell organism that is neither virus nor bacterium)

- Canine reovirus

- Canine respiratory coronavirus.

The classical combination for uncomplicated kennel cough is infection with parainfluenza or adenovirus type 2 in combination with Bordetella bronchiseptica.

Infections involving the distemper virus, Mycoplasma species, or canine influenza are more likely to progress to pneumonia, and pneumonia can readily result in any dog or puppy that is sufficiently young, stressed, or debilitated.

Not sure what a Coughing Dog sounds like?

Dogs can make assorted respiratory sounds. Usually, a cough is recognizable but it is important to be aware of another sound called a reverse sneeze. The reverse sneeze is often mistaken for a cough, a choking fit, sneezing, retching, or even for some sort of respiratory distress. The reverse sneeze is a post-nasal drip or tickle in the throat. It is considered normal, especially for small dogs, and only requires attention if it is felt to be “excessive”. The point here is to know a cough when you hear one. A cough can be dry or productive, meaning it is followed by a gag, swallowing motion, and the production of foamy mucus (not to be confused with vomiting). Here are some videos that might help.

Coughing Dog (with Productive Cough): Dixon has kennel cough

Note: We have received a great deal of emails from people who have viewed this video, compared it to what their own dog is doing, and concluded their dog has kennel cough. This video is meant to demonstrate coughing in general. It is important to note that there are many causes of coughing and the nature of the cough does not generally reflect on its cause.

Reverse Sneezing Dog: Maggie reverse sneezes

How Infection Occurs

An infected dog sheds infectious bacteria and/or viruses in respiratory secretions. These secretions become aerosolized and float in the air where they can be inhaled by a healthy dog. Obviously, crowded housing and suboptimal ventilation play important roles in the likelihood of transmission but organisms may also be transmitted on toys, food bowls, or other objects.

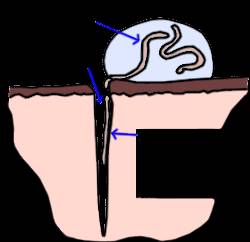

The normal respiratory tract has substantial safeguards against invading infectious agents. Probably the most important of these is what is called the mucociliary escalator. This safeguard consists of tiny hair-like structures called cilia that protrude from the cells lining the respiratory tract and extend into a coat of mucus above them.

The cilia beat in a coordinated fashion through the lower and more watery mucus layer called the sol. A thicker mucus layer called the gel floats on top of the sol. Debris, including infectious agents, gets trapped in the sticky gel and the cilia move them upward toward the throat where the collection of debris and mucus may be coughed up and/or swallowed.

The mucociliary escalator is damaged by the following:

- shipping stress

- crowding stress

- heavy dust exposure

- cigarette smoke exposure

- infectious agents (as listed previously)

- cold temperature

- poor ventilation.

Without this, a fully functional mucociliary escalator or invading bacteria, especially Bordetella bronchiseptica, the chief agent of kennel cough, may simply march down the airways unimpeded.

Bordetella bronchiseptica organisms have some tricks of their own as well:

- They can bind directly to cilia, rendering them unable to function within 3 hours of first contact.

- They secrete substances that disable the immune cells normally responsible for consuming and destroying bacteria.

Because it is common for Bordetella to be accompanied by at least one other infectious agent (such as one of the viruses listed below), kennel cough is a complex of infections rather than infection by one agent.

Classically, dogs get infected when they are kept in a crowded situation with poor air circulation and lots of warm air (i.e., a boarding kennel, vaccination clinic, obedience class, local park, animal shelter, animal hospital waiting room, or grooming parlor). In reality, most causes of coughing that begin acutely in dogs are due to infectious causes and usually represent some form of kennel cough.

The incubation period is 2 to 14 days. Dogs are typically sick for 1 to 2 weeks. Infected dogs shed Bordetella organisms for 1 to 3 months following infection.

How is a Diagnosis Made?

A coughing dog that has a poor appetite, fever, and/or listlessness should be evaluated for pneumonia.

Usually, the history of exposure to a crowd of dogs within the proper time frame, plus typical examination findings (coughing dog that otherwise feels well) is adequate to make the diagnosis. Radiographs show bronchitis and are particularly helpful in determining if there is a complicated pneumonia.

Recently, PCR (polymerase chain reaction) panels have become available in many reference laboratories. Using technology to amplify the presence of DNA in a swab, the lab is able to test for most of the kennel cough infectious agents listed. This knowledge is helpful in guiding therapy and understanding expectations.

How is Kennel Cough Treated?

An uncomplicated case of kennel cough will go away by itself. Cough suppressants can improve patient comfort while the infection is resolving. The dog should be clearly improved, if not recovered, after about a week. That said, several infectious agents in the kennel cough complex are more intense and can cause minor bronchitis to progress to pneumonia, which is a potentially life-threatening disease. Given this possibility, antibiotics are frequently prescribed to kennel cough patients to prevent or curtail pneumonia before it warrants hospitalization.

It is important to distinguish an uncomplicated case of kennel cough from one complicated by pneumonia for obvious reasons. The uncomplicated cases will not have a fever or appetite loss, nor will they be listless. As mentioned, they will seem normal except for coughing. Dogs with pneumonia appear sick.

Prevention through Vaccination

Vaccination is only available for Bordetella bronchiseptica, canine adenovirus type 2, canine parainfluenza virus, canine distemper, and canine influenza. Infections with other members of the kennel cough complex cannot be prevented. Vaccine against adenovirus type 2, parainfluenza, and canine distemper is generally included in the basic puppy series and subsequent boosters (the DHPP or distemper-parvo shot).

For Bordetella bronchiseptica, vaccination can either be given as a separate injection or as a nasal immunization. There is some controversy regarding which method provides a better immunization or if a combination of both formats is best.

Nasal Vaccine

Intranasal vaccination may be given as early as 3 weeks of age and immunity generally lasts 12 to 13 months. The advantage is that local immunity is stimulated right at the site where the natural infection would try to take hold.

It takes four days to generate a solid immune response after intranasal vaccination, so it is best if vaccination is given at least four days prior to the exposure. Some dogs will have some sneezing or nasal discharge in the week following intranasal vaccination; this should clear up on its own. As a general rule, nasal vaccination provides faster immunity than injectable vaccination.

Nasal vaccines for Bordetella generally also include a vaccine against parainfluenza virus and some also include a vaccine against adenovirus type 2.

Oral Vaccine

An oral vaccine is available for Bordetella bronchiseptica (but not adenovirus or parainfluenza). The idea is that it is easier to give the vaccine with a syringe in the mouth – just inside the cheek – and there is no concern about sneezing out some of the vaccine. The oral vaccine can be given to puppies as young as 8 weeks of age. The vaccine is given annually.

Injectable Vaccine

Injectable vaccination is a good choice for aggressive dogs who may bite if their muzzle is approached. For puppies, injectable vaccination provides good systemic immunity as long as two doses are given (approximately one month apart) after age 4 months. Boosters are generally given annually. Some dogs experience a small lump under the skin at the injection site. This should resolve without treatment.

Vaccination is not useful in a dog already incubating kennel cough.

Bordetella bronchiseptica vaccination may not prevent infection. In some cases, vaccination minimizes symptoms of illness but does not entirely prevent infection. This is true whether nasal, oral or injectable vaccine is used.

Dogs that have recovered from Bordetella bronchiseptica are typically immune to reinfection for 6 to 12 months.

What if Kennel Cough doesn’t Improve?

As previously noted, this infection is generally self-limiting. It should be at least improved partially after one week of treatment. If no improvement is seen after that week, a re-check exam (possibly including chest radiographs) would be a good idea. Failure of kennel cough to resolve suggests an underlying condition. Kennel cough can activate a previously asymptomatic collapsing trachea or the condition may have progressed to pneumonia. Alternatively, there may be another disease afoot entirely such as non-infectious bronchitis, congestive heart failure, or some other condition that causes coughing.

If you have questions about a coughing dog, do not hesitate to bring them to your veterinarian.