Causes of Blindness in Dogs and Cats

Owners may notice their pet is disoriented, bumping into objects and struggling to find food and toys. These all may be signs of blindness. There are many potential causes of blindness in dogs and cats. However, before discussing what leads to vision loss, it helps to understand how the eye functions.

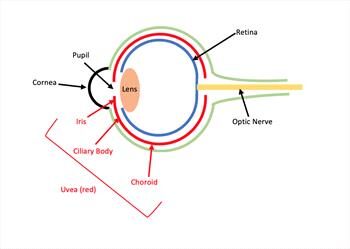

The eye acts like a camera that takes pictures and sends them to the brain for interpretation. Light reflecting off an object enters the eye through the cornea, which is like the eye’s windshield and helps focus light onto the retina. It then passes through a central black hole called the pupil.

The iris, which is the colored part of the eye, surrounds the pupil and regulates how much light passes through it. Behind the iris and pupil is the lens, a transparent structure that also focuses light onto the retina. The retina converts the light into nerve impulses, which travel to the brain through the optic nerve. The brain interprets these impulses into an image. Abnormalities in these and other structures of the eye may lead to blindness.

Some of the more common causes of blindness in dogs and cats include the following.

- Uveitis: Uveitis is a painful condition in which the uvea becomes inflamed. The uvea is a blood vessel-rich tissue consisting of the iris, the ciliary body (which produces fluid inside the eye) and the choroid (which nourishes the retina). Causes of uveitis include infections such as feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) and tick-borne ehrlichiosis, tumors, immune-mediated conditions, eye trauma, toxins and eye irritants.

- Cataracts: A cataract is a cloudiness in the lens. The lens is supposed to be transparent to allow light to pass through, but cataracts impair this function. Cataracts may affect only a small part of the lens initially, but progress to affect more of the lens over time. The most common cause of cataracts in cats is uveitis, while genetics and diabetes are the two most common causes in dogs. Other causes include eye trauma, toxins, nutritional deficiencies, radiation, electric shock and age-related degeneration.

- Glaucoma: Glaucoma is increased pressure in the eye. In a healthy eye, the volume of fluid that goes in and out of the eye is balanced to maintain a normal eye pressure. In glaucoma, a problem draining that fluid causes the eye pressure to rise, a condition that can quickly and painfully cause loss of sight. Primary glaucoma results from genetics while secondary glaucoma results from conditions such as uveitis, eye tumors and anterior lens luxation (see section on lens luxation).

- Retinal detachment: The retina is a 10-layered structure that converts light signals into nerve impulses that are sent to the brain for interpretation into an image. When specific layers of the retina separate or detach from one another, the retina can no longer carry out this function properly, resulting in impaired vision. Causes of retinal detachment include genetics, trauma, tumors, infections, immune-mediated conditions, uveitis, eye surgery and high blood pressure.

- Progressive retinal atrophy (PRA): PRA is an inherited disease that occurs in dogs and more rarely in cats. In pets with PRA, the retina degenerates over time, leading to blindness. In most cases, the pet is initially blind only in low-light conditions, but will eventually become blind in all conditions. Cataracts may also accompany PRA in some dogs.

- Sudden acquired retinal degeneration syndrome (SARDS): This syndrome is a disease in dogs in which the retina rapidly and irreversibly deteriorates, leading to blindness within days to months. The cause of SARDS is unknown.

- Optic neuritis: Optic neuritis is inflammation of the optic nerve, which carries impulses from the eye to the brain to be interpreted as images. Dogs and cats affected by this condition generally end up with partial or complete blindness. Causes of optic neuritis include such infections as distemper in dogs and cryptococcosis, a systemic fungal infection, in cats. Inflammation, immune-mediated conditions, toxins such as rodenticides, eye trauma and tumors are other potential causes.

- Lens luxation: The lens is normally held in position by fine ligaments. If these ligaments fail, then the lens shifts – or luxates – from its normal position. A forward shift can block circulation of the eye’s fluid and quickly lead to painful glaucoma. A backward shift is not as immediately harmful, but secondary glaucoma and retinal detachment can occur. Terrier breeds are predisposed to primary, inherited luxations. Lens luxation may also occur due to cataracts, glaucoma, trauma, tumors, and uveitis.

- Corneal diseases such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, pigmentary keratitis, and pannus will completely scar the cornea if untreated.

If you notice any signs of blindness or changes in your pet’s eyes, take your pet to the veterinarian. Oftentimes, older dogs and cats develop an age-related cloudiness in their eyes that is usually harmless to vision. However, it can look similar to a cataract, so it is still worth getting checked by a veterinarian to make certain it’s harmless.