Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever in Dogs

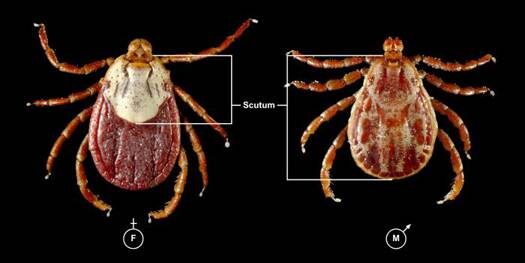

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii. This intracellular parasite is transmitted to dogs through the bite of an infected tick. The ticks that can transmit RMSF are the Rocky Mountain wood tick, the American dog tick, and the brown dog tick.

In the United States, RMSF is most common in the southern Atlantic states, western central states, and areas of the mid-Atlantic and southern New England coastal states. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), only about 1 to 3 percent of the tick population carries R. rickettsii, even in those geographic areas.

Prior research indicated that the infected tick must be attached for at least 2 hours in order to transmit disease. Research in Brazil demonstrated that unfed ticks had to be attached for more than 10 hours for transmission to occur, whereas fed ticks could transmit disease within as little as 10 minutes after attachment. These results may indicate that transmission across all tick species could occur earlier than once thought, depending on when the tick has last eaten. Transmission of the Rickettsia can then occur due to the bite or from exposure to the parasite while handling the tick.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs will show up 2 to 14 days after the bite occurred. The parasite creates an inflammation of the body’s small blood vessels, which results in damage to all the organs of the body.

Common signs include fever, lethargy, inappetence, pain, eye/nose discharge, nosebleed, cough, enlarged lymph nodes, lameness, skin necrosis/sloughing, hemorrhage, and peripheral swelling. Petechial hemorrhages (tiny hemorrhages in the skin) will occur in about 20% of affected dogs. Up to one third of the infected dogs will have central nervous system signs (lack of voluntary coordination of muscle movements, weakness, balance problems, cranial nerve abnormalities, seizures, stupor, spinal pain, etc.). Any organ in the body may be affected and the clinical signs may be mild or severe enough to result in death.

Diagnosis

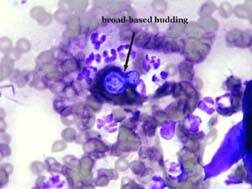

Diagnostic tests for RMSF include blood tests looking for severely low platelet count, plus coagulation profiles, blood chemical analysis, and serology. (Paired titers, from blood samples taken 14 to 21 days apart, are often needed, but a single high titer in dogs that have clinical signs is consistent with an active infection.) Response to antibiotic therapy is suggestive, but not diagnostic.

Treatment/Management

Specific treatment relies on the use of appropriate antibiotics. Response to the antibiotics usually is seen within 24 to 48 hours, although advanced cases may not respond at all to treatment. The most common antibiotics used are tetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline. Chloramphenicol is usually reserved for pregnant bitches or young puppies. Fluoroquinolones, such as enrofloxacin, have shown efficacy, but their use is generally restricted to older animals. Side effects to any of the antibiotics may be seen. Your veterinarian will choose the antibiotic that best suits your pet’s age, pregnancy status, etc.

Blood transfusions to treat anemia and other supportive therapies may be needed.

Prognosis

Prognosis is excellent in dogs that are diagnosed and treated early and who have no complications. Lifelong immunity often occurs after the infection is cleared.

More severely affected patients are at higher risk for complications, such as kidney disease, neurological disease, vasculitis, and coagulopathies. Prognosis is guarded for patients that have complications.

Prevention

Limit your dog’s exposure to ticks and tick-infested areas.

Inspect your dog closely for ticks. The sooner you can remove a tick after it attaches, the better the chance that the organism will not have had time to become infective. Wear gloves when removing ticks, as the infective organism can get into your body through abrasions, cuts, etc. You can also use a tick remover tool.