No Bones About It – Chewing Bones is Bad for Dogs’ Teeth

The Food and Drug Administration warned pet owners about bones and bone treats to include not only harmful bacteria (E.coli and Salmonella) that dogs can get and pass on to humans but the actual damage caused by the bone’s trauma to a dog’s teeth.

Other issues can occur with bones, such as blocked intestines, choking, wounds in the mouth, vomiting/diarrhea, and rectal bleeding (some of which could be fatal if not treated promptly).

Are Any Bones Safe for My Dog’s Teeth?

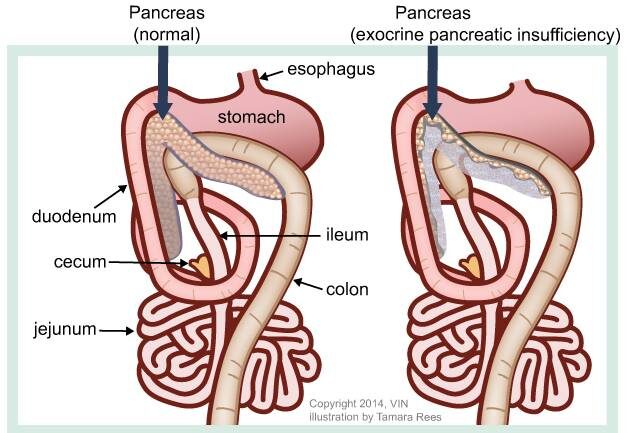

No. Steak bones are too hard for teeth. Antlers are worse than bones because they’re even harder. Poultry bones – chicken, turkey, and duck – are awful because they are full of air and thus splinter easily. The pieces can get stuck in your dog’s palate (roof of the mouth) and cause infection or get stuck in the esophagus or intestines, most of which requires a surgical fix.

What Happens if My Dog’s Teeth Are Injured by Bones? How Will I Know if There is a Problem?

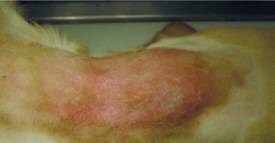

For many dogs, broken teeth do not show signs of discomfort even though they experience pain like humans. Some show apparent signs and symptoms of disease, including an open tract below the eye or under the chin that may be draining.

When the nerves die, the pain decreases until infection sets in. Signs relating to dental disease from a broken tooth include:

- chewing on one side;

- dropping food from the mouth when eating;

- excessive drooling;

- grinding teeth;

- pawing at the mouth;

- facial swelling;

- fistulous tract below the eye or under the lower jaw;

- regional lymph node enlargement;

- shying away when the face is petted;

- refusing to eat hard food;

- refusing to chew on hard treats or toys.

Treatment for Broken Teeth

When presented with a tooth that is fractured and has pulp exposure (complicated tooth fracture), your veterinarian essentially has two choices:

- Extract the tooth.

- Refer to a veterinary dental specialist to perform treatment, which usually allows the tooth to be saved and returned to function. Specific treatment depends on the severity of damage to the tooth structure and if any other disease is affecting the tooth, and the functional significance of the tooth.

Types of Tooth Damage

- Enamel fracture: A fracture with loss of crown substance confined to the enamel

- Complicated crown fracture: A fracture of the crown that exposes the pulp

- Uncomplicated crown-root fracture: A fracture of the crown and root that does not expose the pulp

- Complicated crown-root fracture: A fracture of the crown and root that exposes the pulp

- Root fracture: A fracture involving the root

How Severe is the Damage to the Tooth?

Some fractures are limited to the enamel and require little or no therapy; others involve dentin and might not require endodontic care; others expose enamel, dentin, and pulp and require root canal care or extraction. The goal of endodontic care is to return the tooth to function if possible, and if not, extract the tooth to prevent further pain.

How Important is the Tooth?

The upper and lower canines (eye teeth) are the most common teeth broken, followed by the incisors and the upper cheek teeth.

Although endodontic care can be performed on any tooth, the canines and maxillary fourth premolars generally are the only teeth where endodontic therapy would be considered due to the importance of the tooth and ease of pulp chamber access.

Age of the Patient

The age of the patient is also essential when choosing endodontic therapy options. Canine teeth of patients younger than twelve months of age may have open root apices (the tip of the tooth’s root). Lower molar teeth generally have closed apices by seven months of age. Standard root canal therapy is not performed on teeth with open root apices because appropriate sealing of the apex cannot be assured.

Treatment options for teeth with open root apices include:

- Vital pulp therapy (partial coronal pulpectomy, direct pulp capping, and restoration) to promote the preservation of vital pulp tissue or

- A procedure called apexification is used to stimulate root development if the pulp is dead. Teeth with pulp exposure and closed root apices can be treated with standard root canal therapy.

Age of the Fracture

The age of the fracture affects endodontic treatment. Inflammation occurs less than two mm from the exposure site shortly after pulp exposure. In acute (sudden) fractures, the pulp appears pink or red at the fracture surface. The pulp of a long-standing fracture will appear brown or black. Healthy pulp tissue can be found several millimeters deeper within the pulp, which might respond to vital pulp procedures (i.e., vital pulp therapy).

In the mature animal that has an acutely fractured tooth with a closed apex, standard root canal therapy results in a more predictable outcome compared to vital pulp therapy.

Aftercare Support

Tooth support is critical to the long-term success of endodontic treatment. If obvious periodontal disease is present before therapy, victory will be unlikely unless epic measures are taken, and strict home care is provided.

Dogs love to chew. To find out what products are safe and effective in decreasing the accumulation of plaque and tartar, discuss with your veterinarian.