When a patient, human or non-human, is said to have kidney failure, renal insufficiency, or even chronic renal failure, what most people are talking about is a toxin build up when the kidney cannot adequately remove the body’s harmful wastes. This toxic state is called uremia and is associated with nausea, appetite loss, weight loss, listlessness, and other unpleasant issues. It is also not the kind of kidney disease we are going discuss here.

Glomerular disease is a completely different kind of kidney disease and may not involve any toxin build up at all. Glomerular disease is one of protein loss.

What is a Glomerulus Anyway?

Consider for a moment what an important resource protein is to your body. Your blood, for example, is full of necessary circulating proteins handling clotting, fluid balance, transporting other chemicals etc. Your body went to a lot of trouble to build those proteins and you can’t afford to waste them. If you were to lose them, your body would have to break down muscle in order to recreate them because that is how important they are.

On the other hand, your blood carries an assortment of metabolic wastes that you need to get rid of. You need to filter out these bad materials without losing what is valuable. The millions of glomeruli you have are in charge of keeping your blood proteins where they belong — in the blood — while allowing for smaller wastes and extra fluid to filter out and be made into urine. There are other valuables in your blood besides cells and protein, but different areas of your kidney handle those.

The illustration to the right shows the nephron, which is the functional unit of the kidney. There are millions of these making urine every moment of every day. Only about 30 percent of them must be working in order to maintain normal kidney function. The rest form a back up system so that we will have plenty of extra nephrons should some of them get plugged with debris, damaged by scarring or infection, or starved for oxygen during a traumatic event.

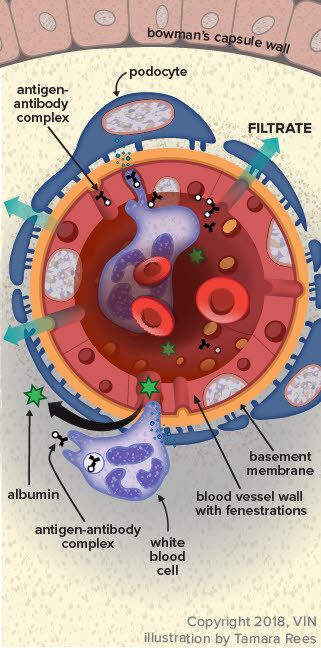

The glomerulus, which in a way looks like a little dandelion tuft, is where our interest lies today. Blood flows through an afferent arteriole into the glomerulus. Inside the glomerular tuft, the blood vessel narrows into a complicated spiral of tiny capillaries, so small that the blood cells pass through single file. The capillaries are gripped by cells called podocytes. Like hands, the podocytes have tiny fingers (ironically called foot processes) that encase the capillaries. Fluid and small molecules can flow in between the fingers while cells and large molecules like proteins cannot pass through.

The cells and large molecules/proteins exit the glomerulus through an efferent arteriole and return to normal circulation. This first step in filtration is driven both by blood pressure as well as by the protein content of the blood.

Now imagine what would happen if there were holes punched in that filtration system so that protein can pass through the fingers. This is what happens in glomerular disease.

How does the Glomerulus get Leaky?

Sources of chronic inflammation are believed to be the ultimate cause of the problem. The chronic inflammatory state leads to the circulation of antigen:antibody complexes in the blood and these complexes stick in delicate glomerular membranes like flies in fly paper. Once stuck there, they call in other inflammatory cells and soon a hole is eaten into the membrane by the ensuing reaction. The holes in the filtration membranes are big enough for proteins to traverse.

There are many possible sources of chronic inflammation that could be generating antigen:antibody complexes. Chronic ear or skin infections could be the cause. Long-standing dental disease could do it.

A latent, more internal infection might be the cause (such as heartworm, Lyme disease, prostate infection, or Ehrlichiosis). Even a tumor might generate enough of the immune system’s attention to lead to this sort of reaction. If it is at all possible to identify and resolve the underlying cause of inflammation, this should be done as other therapy is unlikely to fully resolve the protein loss.

How is the Diagnosis Made?

There are several common scenarios that might lead to the diagnosis but they all boil down to one or both of two findings: excess urine protein found on a routine urinalysis and/or low albumin found on a blood test.

Let’s start with excess urine protein found on a routine urinalysis.

A urinalysis examines a urine sample for some of its chemical contents and properties. Protein content is one of the parameters that is checked and reported as a small, medium or large amount. On a urinalysis report this will be designated as “+,” “++,” or “+++.”

This seems like it would be easy enough to interpret but unfortunately there is more to the story. A small amount of protein in a well-concentrated sample may be normal while the same amount of protein in a dilute sample would be highly significant. How dilute or concentrated the urine is depends on the patient’s water consumption, and we need a method to examine urine protein that is independent of the water consumption. Further, we need to determine if any protein in the urine is truly coming from the kidneys; after all, a bladder infection or other bladder condition might generate urine protein. To help distinguish renal protein loss, the rest of the urinalysis will be helpful. When your veterinarian is confident that other issues with the urinary tract have been excluded, it is time for a urine protein:creatinine ratio (we will come back to this).

Low Blood Albumin Level found on a Blood Panel

Albumin is one of those proteins that the body really wants to conserve and here’s why. There are plenty of substances the body needs to circulate that simply are not water soluble. How do we circulate these things if they won’t dissolve in water? We bind them to a carrier protein that will circulate and carry them as if they were commuters on a city bus. The albumin molecule is that city bus, carrying important biochemicals around your body.

There’s more. Albumin also is important in keeping water in the bloodstream. This sounds odd but blood is basically a liquid and without enough water, it sludges and clots abnormally. Furthermore, if water is not held in the vasculature, it leaks into other body cavities such as the chest and abdomen, filling these cavities with liquid.

Your body prioritizes the maintenance of its albumin levels and will not allow them to drop. When the albumin levels are down, a serious protein loss is afoot. It could be intestinal or liver-related, but glomerular protein loss is going to be one of the first conditions to rule out. If there is no protein in the urine, the focus shifts to other organs but if there is protein in the urine, it must be quantified and that means there is a urine protein:creatinine ratio.

Interpretation of the Urine Protein: Creatinine ratio

The urine protein:creatinine ratio compares the amount of protein in the urine to the amount of creatinine, one of the metabolic wastes filtered by the kidneys. By using this ratio, it does not matter how dilute the urine is or how concentrated it is. The ratio allows for protein loss to be quantified and then we can tell how significant the protein loss actually is. If the urine protein: creatinine ratio is found to be abnormal, ideally it is repeated in 2 to 4 weeks to be sure that the protein loss is persistent, but this depends on how high the ratio is and whether or not there is a known inflammatory condition that would be expected to damage the glomeruli.

Determining how serious a patient’s protein loss is depends on overall kidney function as well. In other words, a protein-losing kidney that is effectively removing the daily load of toxins and wastes is in less trouble than a protein-losing kidney that is failing.

The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) considers a urine protein:creatinine ratio of greater than 0.5 for dogs or 0.4 for cats to be abnormal, and if it is persistent, then further diagnostics and treatment are recommended.

Depending on how your pet responds to the therapies above, a biopsy may be recommended. Biopsy is most commonly recommended for patients with UPC ratios more than 3.5 or with significant proteinuria combined with low albumin levels or high blood pressure.

The goal of treatment is to reduce the UPC ratio to below 0.5 or to reduce it by at least 50%. Higher reductions are sought for cats (see later).

Ratios greater than 3.5 are particularly concerning and require more aggressive treatment and more extensive diagnostics. These patients have an increased risk of abnormal blood clotting and generally have more extensive kidney damage.

The urine protein: creatinine ratio varies by up to 30% above or below baseline as a matter of course. A significant change in the ratio caused by disease progression (up) or response to therapy (down) must be greater than 30%.

If Intervention is Recommended what Does that Mean?

Adding omega 3 fatty acids to the regimen appears to improve the protein loss situation and supplementation is recommended. Most renal diets are already fortified with these anti-inflammatory fats but additional use is felt to be beneficial.

Low Protein, Low Sodium Diet

Most commercial renal diets would fit in this category. It seems paradoxical that a disease that causes body protein to be lost would be treated with a protein-restricted diet but, in fact, supplementing protein causes albumin to drop faster.

ACE Inhibitor

These medications have been shown to reduce renal protein loss. Typically enalapril is recommended for dogs and benazepril is recommended for cats. These medications inherently reduce blood flow to the kidneys so care must be taken in patients with elevated creatinine ratios to be sure the uremia does not worsen. Lower doses are used and monitoring becomes more important.

Omega 3 Fatty Acid Supplementation

Most commercial renal diets are fortified with omega 3 fatty acids. These anti-inflammatory fats have been shown to improve survival of dogs with renal disease. It is still unclear how helpful they are for cats but studies are ongoing.

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs)

Angiotensin II receptor blockers are becoming more popular in human medicine and their use is trickling down to manage canine glomerular disease. These medications work with ACE inhibitors to further help reduce urinary protein loss though they can also be used alone. Like the ACE inhibitors, they not only reduce urine protein loss but also lower blood pressure as well and seem to have some effect on reducing the clotting tendency. They are new to veterinary medicine and protocols are still being worked out. The two commonly used medications are losartan and telmisartan.

Spironolactone

Aldosterone is the hormone that acts on the kidney to retain sodium and water and get rid of potassium. Spironolactone is an antagonist of this hormone, which means it increases urine production, retains potassium and removes sodium. In humans, it has been found to reduce urine protein loss by 34 percent, which makes it an attractive medication for this situation especially in patients with nephrotic syndrome (see below). In dogs it might be used when ACE inhibitors or ARBs have not controlled the proteinuria. It is not a medication for cats.

The goal in managing urine protein loss is a 50% reduction in urine protein:creatinine ratio for dogs and a 90% reduction in urine protein:creatinine ratio for cats. A combination of the above medications is likely to be prescribed, and urine and blood test monitoring will be periodically (at least quarterly) recommended in hope of achieving and finally maintaining these results.

Nephrotic Syndrome

In severe cases, a complication called nephrotic syndrome can result due to the extreme urinary protein loss. Nephrotic syndrome is defined as the combination of: 1) significant protein loss in urine; 2) low serum albumin; 3) edema or other abnormal fluid accumulation; or 4) elevated blood cholesterol level. This is a severe complication of glomerular disease and suggests a poor prognosis, especially if creatinine levels are elevated in the blood. High blood pressure is a common complication of nephrotic syndrome. Patients also tend to form inappropriate blood clots (embolism) that can lodge in small blood vessels, causing loss of circulation to entire organs or sections of organs. Nephrotic syndrome is an advanced state of urinary protein loss and must be treated aggressively.

Biopsy the Kidney?

There are pros and cons to this relatively invasive test. The kidney receives 25 percent of the blood supply at any given time, which means it is highly vascularized and can bleed in an extreme way. Blood transfusion is needed for 10 percent of dogs and 17 percent of cats having this procedure, and a three percent mortality rate has been reported. So why take the chance on this procedure? The main reason is to obtain information on prognosis. There are different types of glomerular disease and glomerular inflammation, all of which may have different associated expectations. There is a type of glomerular disease called amyloidosis that involves abnormal protein (called amyloid) infiltrating the kidneys and has a much more progressive and damaging course. Approximately 50 percent of glomerular disease patients have diseases that can benefit from immune-suppressive therapy but the only way to identify these patients is with a biopsy.

Conclusion

When the kidney cannot retain blood proteins, the body loses its ability to carry out normal blood functions. In an attempt to replace these proteins, muscle is broken down and the patient becomes debilitated. Maintaining proper nutrition and using medication to reduce the protein loss are crucial to managing this form of kidney disease. It is important for the pet owner to keep up the monitoring schedule and to stay in contact with the veterinarian as to the pet’s progress and response to therapy.

In Summary

- Glomerular disease is one broad type of kidney disease in which the primary problem is loss of renal proteinuria. Glomerulonephritis is one broad classification of kidney inflammation. It usually results in protein loss in urine. There are subtypes that can be determined by specialist pathologists based on renal biopsy.

- It is not typical Glomerular disease differs somewhat from “classic” kidney failure renal disease, although it glomerular disease can lead to chronic kidney disease if undetected.

- In the kidney, there are a million nephrons that make urine every minute of the day and send that urine to the bladder and out of the body through a filtration system. A body only needs approximately 30% of those nephrons working correctly for normal kidney function, at least as far as veterinarians could detect with typical lab tests. The rest are a backup system called the functional reserve.

- Inflammatory cells punch small holes along the filtration route. Those holes are big enough for proteins to pass through.

- Sources of chronic inflammation are believed to cause the problem, possibly stemming from issues such as chronic ear or skin infections, dental disease, heartworm disease, vector-borne diseases like Lyme disease, or feline immunodeficiency.

- Diagnosis is suspected by excess urine protein found in urine, and/or low albumin found on a blood test. Definitive diagnosis of glomerulonephritis and its specific type requires a kidney biopsy.

- When the kidney cannot retain blood proteins, the body cannot carry out normal blood functions. In an attempt to replace these proteins, muscle is broken down and the patient becomes debilitated.

- The urine protein:creatinine ratio (UPC) found in a urine test compares the amount of protein in the urine to the amount of creatinine, a metabolic waste filtered by the kidneys. The ratio tells what the magnitude of the protein loss actually is. A persisting, reproducible urine protein:creatinine ratio of greater than 0.5 for dogs or 0.4 for cats is too high. Mild elevations can be due to causes other than glomerulonephritis.

- Determining how serious the protein loss also depends on overall kidney function. A protein-losing kidney that is still effectively removing the daily load of toxins and wastes is in less trouble than one that is failing. Once the urine protein:creatinine reaches a certain ratio, a biopsy may be recommended. Ratios greater than 3.5 (typical US units) are particularly concerning.

- The best treatment is when a specific cause is found, such as a systemic infectious disease, and that disease can be successfully treated. However, sometimes despite extensive searching with imaging and blood tests, no underlying cause can be found.

- One goal is to reduce the urine protein:creatinine ratio to below 0.5 or to reduce it by at least 50% in dogs and 90% in cats.

- Potential interventions expected to help specifically with proteinuria include: omega-3 fatty acid supplementation; a controlled protein, low sodium diet; and RAAS inhibition (with drugs called ARBs or ACEIs). Accompanying hypertension, when present, may require additional treatment.

- In severe cases, a complication called nephrotic syndrome can result due to extreme urinary protein loss. The prognosis for this complication is comparatively poor, although it does depend on whether the problem developed acutely or chronically.

- A kidney biopsy can be informative about a prognosis and suggest whether additional treatments are expected to help. Since immunosuppressive treatments can also do harm, biopsy is usually recommended to justify trying that type of medication. Biopsy can be expensive and requires pre-planning to make it safe. For sample evaluation to be truly valuable, the specimens are analyzed by a specialist veterinary nephropathologist.

- It is important for you to keep up the monitoring schedule and stay in contact with your veterinarian.