What is Osteosarcoma?

Osteosarcoma is by far the most common bone tumor of dogs, usually striking the leg bones of larger breeds. Osteosarcoma usually occurs in middle aged or elderly dogs but can occur in a dog of any age; larger breeds tend to develop tumors at younger ages.

- Osteosarcoma can develop in any bone but the limbs account for 75-85 percent of affected bones. Osteosarcoma of the limbs is called appendicular osteosarcoma.

- It develops deep within the bone and becomes progressively more painful as it grows outward and the bone is destroyed from the inside out. The lameness goes from intermittent to constant over 1 to 3 months. Obvious swelling becomes evident as the tumor grows and normal bone is replaced by tumorous bone.

- Tumorous bone is not as strong as normal bone and can break with minor injury. This type of broken bone is called a pathologic fracture and may be the finding that confirms the diagnosis of bone tumor. Pathologic fractures will not heal and there is no point in putting on casts or attempting surgical stabilization.

How do we Know my Dog Really has an Osteosarcoma?

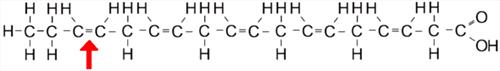

Radiographs (x-rays)

The lytic lesion looks like an area of bone has been eaten away. One of the first steps in evaluating a persistent lameness is radiography (x-rays). Bone tumors are tender so it is usually clear what part of the limb should be radiographed. The osteosarcoma creates some characteristic findings.

- The sunburst pattern – shows as a corona effect as the tumor grows outward and pushes the more normal outer bone up and away.

- A pathologic fracture may be seen through the abnormal bone.

- Osteosarcoma does not cross the joint space to affect other bones in the joint.

Radiography is almost completely diagnostic in most cases, but there are a few other far less common conditions that can mimic the appearance of a bone tumor, so a confirming test is going to be needed if one is to be complete. If a basic blood panel and urinalysis haven’t been done, this would also be a good time to do so as basic information about liver and kidney function will be needed for treatment regardless of whether this turns out to be a bone tumor or not; plus, a tissue sample from the bone is needed for confirmation (see later).

Tissue Sampling: Biopsy and Needle Aspirate

Radiographs are close to being confirmatory but still they are not definitive. Since life and death decisions are going to be made, it is best to obtain a tissue sample for confirmation. This can be done by either biopsy or by needle aspirate.

Biopsy

A small piece of bone can be harvested surgically. The bone is preserved, sectioned, and examined under the microscope to confirm the diagnosis of osteosarcoma. There are several problems associated with this diagnostic. Sometimes a bone tumor is surrounded by an area of bone inflammation and it may be difficult to get a representative sample. The tiny hole that results when a core of bone is removed can create a weak spot and the bone can actually break. Even if the procedure goes well, often there is increased pain and lameness for the patient afterwards. With so many potential problems, most specialists have switched to needle aspirate for diagnosis.

Needle Aspirate

With needle aspirate, a large bore needle is inserted into the area of the tumor and cells are withdrawn for analysis. A full core of bone is not removed, just a sampling of cells. This is usually sufficient to confirm osteosarcoma. If there is ambiguity, certain stains can often settle any questions the pathologist may have.

With a Diagnosis Confirmed, Staging is the next Consideration

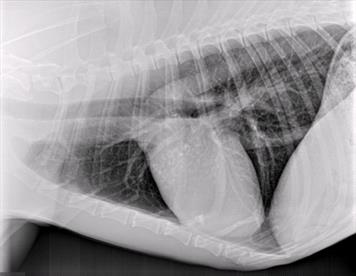

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive tumor and it can be assumed to have spread by the time it is first diagnosed; there is no possibility of preventing spread. That said, how well treatments can be expected to work depend on whether or not the tumor spread has progressed so as to be visible. Because osteosarcoma spreads to the lungs as one of its first stops, chest radiographs are important in checking for visible tumor spread. If there is already visible tumor spread at diagnosis, this changes what treatments are recommended.

Some specialists recommend nuclear imaging of the skeleton to identify any spread to other bones, which might also alter recommendations; however, this form of imaging is not readily available.

What if it isn’t Really an Osteosarcoma?

The location and radiographic appearance of the osteosarcoma in the limb are quite classic but there are a few outside possibilities that should at least be mentioned. Only a few other possible conditions cause similar lesions in bone: the chondrosarcoma, the squamous cell carcinoma, the synovial cell sarcoma, or fungal bone infection.

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma is a cartilage tumor, possibly not as malignant as the osteosarcoma. The chondrosarcoma generally occurs on flat bones such as ribs or skull bones and is not usually found in the limbs. Still, should a chondrosarcoma occur in the limb, treatment recommendations still include amputation of the affected bone and many of the same treatments as for osteosarcoma.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The squamous cell carcinoma is a tumor of the external coating of the bone, called the periosteum. This is a destructive tumor locally but it tends to spread relatively slowly. Again, a bone suspected of malignant tumor should be amputated, and the tissue then analyzed and then treatment adjustments should be made thereafter. The squamous cell carcinoma tends not to arise in the same bone areas as the osteosarcoma; it tends to arise in the jaw bones or in the toe bones.

Synovial Cell Sarcoma This is a tumor of the joint capsule lining. Its hallmark is that it affects both bones of the joint. The osteosarcoma, no matter how large or destructive it becomes, will never cross over to an adjacent bone. Prognosis is much better with amputation with synovial cell sarcoma.

Fungal Bone Infection

Coccidiodes immitis is a fungus native to the lower Sonoran life zone of the southwestern United States. It is the infectious agent of the disease called San Joaquin Valley Fever or just Valley Fever. (More scientifically, the condition is called coccidioidomycosis.) In most cases, infection is limited to a few calcified lymph nodes in the chest and possibly lung disease. In some rare cases, though, the fungus disseminated through the body and can cause a very proliferative bone infection.

The bone infection of coccidiodomycosis grows rapidly and lacks the lytic lesions that are typical of the osteosarcoma. Other fungi, such as Histoplasma capsulatum, also have potential for bone involvement. Pursuit of this possibility makes sense if you live in an area where these fungi are a concern. Disseminated fungal disease is serious and even though this diagnosis is not cancerous, amputating the limb is most likely going to be necessary.

Treatment of osteosarcoma involves two aspects: treating the pain and fighting the cancer’s spread.

How do we Treat the Pain?

Keep in mind that dogs are usually euthanized because of the pain in the affected bone. Treating the pain successfully will allow a dog to live comfortably and extend life expectancy by virtue of extending comfort.

There are two ways to address the pain: amputatating the limb and palliative radiotherapy (usually combined with periodic bisphosphonate infusion treatments).

For most patients, there is one tumor on a leg and no visible tumor spread in the lungs. These are the patients with the best potential results and they are good candidates for amputation. Patients with a lot of arthritis in the other legs or with tumor spread evident in the chest already are probably not candidates for amputation and it may be more appropriate to keep the leg and simply relieve the pain with radiotherapy.

Amputating the Limb

Since the tumor in the limb is the source of pain, it makes sense that amputating the limb would resolve the pain. In fact, this is true. Removing the affected limb resolves the pain in 100 percent of cases. Unfortunately, many people are reluctant to have this procedure performed because of misconceptions.

- While losing a leg is handicapping to a human, losing one leg out of four does not restrict a dog’s activity level. Running and playing are not inhibited by amputation after recovery from surgery. That said, if the remaining legs are arthritic, the stress on them can pose a mobility issue.

- While losing a limb is disfiguring to a human and has social ramifications, dogs are not self-conscious about their image. The dog will not feel disfigured by the surgery; it is the owner that will need to adjust to the dog’s new appearance.

- Median survival time for dogs who do not receive chemotherapy for osteosarcoma is 3 to 5 months from the time of diagnosis regardless of whether or not they have amputation. Do you want your dog’s last 3 to 5 months to be painful or comfortable?

Read a letter about amputation from a veterinarian who sees too many owners who reject the option of amputation out of hand. His letter includes videos of two happy dogs without limbs.

Limb-sparing Surgery (removing the tumor but not the leg)

Limb-sparing techniques developed for humans have been adapted for dogs. To spare the limb and thus avoid amputation, the tumorous bone is removed and either replaced by a bone graft from a bone bank or the remaining bone can be re-grown via a new technique called bone transport osteogenesis. The joint nearest the tumor is fused (i.e., fixed in one position and cannot be flexed or extended.)

- Limb sparing cannot be done if more than 50% of the bone is involved by tumor or if neighboring muscle is involved.

- Limb sparing does not work well for hind legs or tumors of the humerus (arm bone.)

- Limb sparing works best for tumors of the distal radius (forearm bone).

- Complications of limb sparing can include: Bone infection, implant failure, tumor recurrence, and fracture.

While amputation can be viewed as a pain management strategy, limb-sparing is only performed in conjunction with chemotherapy. It is important to keep in mind that grafting of a new bone structure requires healing time and that a great deal of post-operative confinement time is needed (in a patient whose life expectancy is going to be measured in months). For the right patient, limb-sparing can be the best choice but be sure to understand all the details of post-operative care from the specialist.

Palliative Radiotherapy for Pain Control

Sometimes amputation is simply not the right choice and happily there is an effective alternative treatment. Radiation can be applied to the tumor in two, three or four doses, depending on the protocol. Improved limb function is usually evident within the first 3 weeks and typically lasts 2 to 4 months. When pain returns, radiation can be given again for further pain relief if deemed appropriate based on the stage of the cancer at that time.

There are a couple of caveats:

- When pain is relieved in the tumorous limb, there is an increase in activity that can in turn lead to a pathologic fracture of the bone.

- Radiotherapy does not produce a helpful response in about 1/4 of patients. Remember, amputation controls pain in 100 percent of cases but if amputation is simply not an option, there is a 3 out of 4 chance that radiotherapy will control the pain.

Current standard treatment involves pairing palliative radiation with monthly infusions of medications called bisphosphonates.

Bisphosphonates

This class of drug has become the standard of care in humans with bone tumors and have been found helpful in managing osteosarcoma pain in dogs as well. Bisphosphonates act by inhibiting bone destruction, which in turn helps control the pain and bone damage caused by the bone tumor. The most common bisphosphonate in use for dogs has been pamidronate, though a new drug zoledronate is taking its place gradually. Treatment is given as an IV drip over two hours in the hospital every 3 to 4 weeks. In humans, an assortment of potential side effects have emerged (fever, muscle pain, nausea all lasting 1 to 2 days in up to 25 percent of patients, renal disease in certain situations, low blood calcium levels, jaw bone cell death); these issues so far have not panned out as problems for dogs and cats. Bisphosphonates are important in managing bone tumor pain in patients that have no undergone amputation.

Analgesic Drugs

At this time there are numerous analgesic medications available for dogs with this tumor. No single medication, however, is a match for the pain involved in what amounts to a slowly exploding bone. A combination of medications is needed to be reasonably palliative and should be considered only as a last resort if amputation or radiation therapy will not be pursued. There are several types of drugs that can be combined.

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

These are anti-inflammatory pain relievers developed for dogs: carprofen, etodolac, deracoxib, meloxicam, firocoxib, and others. These are typically given once or twice daily in tablet form at home. The patient should have good liver and kidney function in order to take medications of this class.

- Narcotic Pain Relievers

While these drugs do not have anti-inflammatory properties, they are well-known analgesics and have been used in an assortment of forms for thousands of years. They are particularly useful in chronic pain because they do not interact negatively with other pain relievers. Drowsiness is a potential side effect.

- Miscellaneous Supplemental Pain Relievers

There are two drugs that have surfaced as adjunct pain relievers for animals with chronic pain: gabapentin and amantadine. Gabapentin works on neurologic pain and is rapidly surfacing in the treatment of arthritis, surgical pain, and other chronic pain states. Amantadine works by reducing what is called wind up, a phenomenon where nerves become sensitized to pain leading to the experience of pain from stimuli that normally do not cause pain.

These different drugs are often given together to create analgesia to the osteosarcoma patient when amputation and radiotherapy are not going to happen. It is important to realize that there is a limit to how much pain relief can be achieved against a bone tumor with only pills. It will not be long before the pain of this tumor, as evidenced by not using the leg, tenderness to the touch, etc., overpowers the effect of oral medications.

How do we Treat the Cancer?

Osteosarcoma is unfortunately a fast-spreading tumor. By the time the tumor is found, it is considered to have already spread. Osteosarcoma spreads to the lung in a malignant process called metastasis. Prognosis is substantially worse if the tumor spread is visible on chest radiographs, so if you are contemplating chemotherapy, chest radiographs should be taken.

- Chemotherapy is the only meaningful way to alter the course of this cancer.

- Young dogs with osteosarcoma tend to have shorter survival times and more aggressive disease than older dogs with osteosarcoma.

- Elevations of alkaline phosphatase, one of the enzymes screened on a basic blood panel, bode poorly. These dogs have approximately 50% of the survival times quoted below for each protocol.

- A tumor in the lymph nodes local to the leg being amputated also bodes poorly. In the study by Hillers et. al published in the April 15th, 2005 issue of the Journal of the AVMA, median survival was significantly longer (318 days vs. 59 days) in dogs where the tumor was not evident in local lymph nodes at the time of amputation.

Cisplatin (given by IV every 3 to 4 weeks for 3 treatments)

- The median survival time with this therapy is 400 days.

- Survival at 1 year: 30% to 60%

- Survival at 2 years: 7% to 21%

- Giving less than 3 doses does not increase survival time (i.e., if one can only afford one or two treatments, it is not worth the expense of therapy)

- Cisplatin can be toxic to the kidneys and should not be used in animals with pre-existing kidney disease.

Carboplatin (given by IV every 3 to 4 weeks for 4 treatments)

- Similar statistics to cisplatin but carboplatin is not toxic to the kidneys and can be used if the patient has pre-existing kidney disease.

- Carboplatin is substantially more expensive than cisplatin.

Doxorubicin (given IV every 2 weeks for 5 treatments)

- The median survival time is 365 days.

- 10% still alive at 2 years.

- Toxic to the heart. An ultrasound examination is needed prior to using this drug as it should not be given to patients with reduced heart contracting ability.

Doxorubicin and Cisplatin in Combination (both given IV together every 3 weeks for four treatments)

- 48% survival at 1 year

- 30% survival at 2 years

- 16% survival at 3 years.

What is Median Survival Time?

There are a number of ways to statistically evaluate the central tendency of a group. The median is the value at which 50% of the group falls above and 50% of the group falls below. This is a little different from the average of the group, though more people are familiar with this term. When evaluating median survival times, you are looking at a 50% chance of surviving longer than the median and a 50% chance of surviving less than the median.

What Does Chemotherapy Put my Dog Through?

Most people have an image of the chemotherapy patient either through experience or the media and this image typically includes lots of weakness, nausea, and hair loss. In fact, the animal experience in chemotherapy is not nearly as dramatic. After the pet has a treatment, expect 1 to 2 days of lethargy and nausea. This is often substantially helped with medications like Zofran, a strong anti-nausea drug commonly used in chemotherapy patients. These side effects are worse if a combination of drugs is used but the pet is typically back to normal by the third day after treatment. Effectively, you are trading 8 days of sickness for 6 to 12 months of quality life. Hair loss is not usually a feature of animal chemotherapy. In dogs, hair loss may occur in breeds that have continuously growing coats, such as poodles, Scottish terriers, and Westies.

Axial Osteosarcoma

While osteosarcoma of the limbs is the classical form of this disease, osteosarcoma can develop anywhere there is bone. “Axial” osteosarcoma is the term for osteosarcoma originating in bones other than limb bones, with the most common affected bones being the jaws (both lower and upper). Victims of the axial form of osteosarcoma tend to be smaller, middle-aged, and females outnumber males two to one.

In the axial skeleton the tumor does not grow rapidly as do the appendicular tumors, thus leading to a more insidious course of disease. The tumor may be there for as long as two years before it is formally diagnosed. An exception is osteosarcoma of the rib, which tends to be more aggressive than other axial osteosarcomas.

Treatment for axial osteosarcoma is similar to that for the appendicular form: surgery followed by chemotherapy. There is one exception, that being osteosarcoma of the lower jaw. Because of the slower growth of the axial tumor and the ability to remove part or all of the jaw bone with little loss of function or cosmetic disfigurement, it has been reported that 71% of cases survived one year or longer with no chemotherapy at all.

Additional information can be found at Bone Cancer Dogs, Inc., a nonprofit corporation.

Not all veterinarians are comfortable treating osteosarcoma. Discuss with your veterinarian whether referral to a specialist would be best for you and your pet.