Ticks Are Arthropod Parasites for Mammals

Ticks are skin parasites that feed on the blood of their hosts. Ticks like motion, warm temperatures from body heat, and the carbon dioxide exhaled by mammals, so they are attracted to such hosts as dogs, cats, rodents, rabbits, cattle, small mammals, etc. The bite itself is not usually painful, but the parasite can transmit diseases and cause tick paralysis, which is why tick control is so important. (Removing the ticks leads to rapid improvement of the paralysis.)

The minimal amount of time it takes for an attached tick to transmit disease is not known. The time it takes to transmit diseases is affected by the type of disease organism, the species of tick, etc. However, in general, if a tick is removed within 16 hours, the risk of disease transmission is considered to be very low. Therefore, owners can usually prevent disease transmission to their pets by following a regular schedule to look for and remove ticks.

The Tick Life Cycle

Most types of ticks require three hosts during a 2-3 year lifespan. Each tick stage requires a blood meal before it can reach the next stage. Hard ticks have four life stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult.

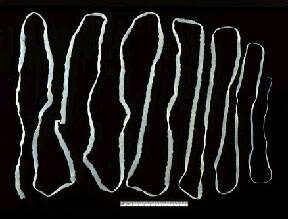

Larvae and nymphs must feed before they detach and molt. Adult female ticks can engorge, increasing their weight by more than 100-fold. After detaching, an adult female tick can lay approximately 3,000 eggs.

During the egg-laying stage, ticks lay eggs in secluded areas with dense vegetation. The eggs hatch within two weeks. Some species of ticks lay 100 eggs at a time, while others lay 3,000 to 6,000 per batch. Once the eggs hatch, the ticks are in the larval stage, during which time the larvae move into the grass and search for their first blood meal. At this stage, they will attach themselves for several days to their first host, usually a bird or rodent, and then fall onto the ground. The nymph stage begins after the first blood meal is completed. Nymphs remain inactive during winter and start moving again in spring. Nymphs find a host, usually a rodent, pet, or human.

Nymphs are generally about the size of a freckle. After this blood meal, ticks fall off the host and move into the adult stage. Throughout the autumn, male and female adults find a host, which is again usually a rodent, pet, or human. The adult female feeds for 8 to 12 days. The female mates while still attached to her host. Both ticks fall off, and the males die. The female remains inactive through the winter and in the spring lays her eggs in a secluded place. If adults cannot find a host animal in the fall, they can survive in leaf litter until the spring.

What are the best ways to deal with these blood-sucking parasites?

Outdoor Environmental Control

Treating the yard and outdoor kennel area with acaricides (tick pesticides) is an important tool in the arsenal against ticks. Some products can be used to spray the outdoor area. However, you should not rely on spraying to reduce your risk of infection.

If you have health concerns about applying acaricides, check with local health or agricultural officials about the best time to

apply acaricides in your area, identify rules and regulations related to pesticide application on residential properties, and consider using a professional pesticide company to apply pesticides at your home.

You can also create a tick-safe zone in your yard by using some simple landscaping techniques that can help reduce tick populations:

- Remove leaf litter.

- Clear tall grasses and brush around homes and at the edge of lawns.

- Place a 3-ft wide barrier of wood chips or gravel between lawns and wooded areas to restrict tick migration into recreational areas.

- Mow the lawn frequently.

- Stack wood neatly and in a dry area. (This discourages rodents who would be used as tick hosts.)

- Keep playground equipment, decks, and patios away from yard edges and trees.

- Discourage unwelcome animals (such as deer, raccoons, and stray dogs) from entering your yard by constructing fences.

- Remove old furniture, mattresses, or trash from the yard that may give ticks a place to hide.

Indoor Environmental Control

If ticks are indoors, flea and tick foggers, sprays, or powders can be used. Inside, ticks typically crawl (they don’t jump) and may be in cracks around windows and doors. A one-foot barrier of insecticide, where the carpeting and wall meet, can help with tick control.

Preventing Ticks from Attaching

If your pet goes outside regularly, you can use some type of residual insecticide on your pet. Talk to your veterinarian about what works best in your geographic area. If you use a liquid spray treatment, cats and skittish dogs typically prefer a pump bottle because of the noise from aerosol cans. Doubling the amount of anti-tick product, or using two at once, may cause toxicity problems.

Any spray insecticide labeled for use on clothing should not be sprayed directly on pets.

Powders are fairly easy to apply, but they can be messy. (Avoid topical powders if your pet has a respiratory condition.) Shampoos are useful only for ticks that are already on your pet. A tick collar might be somewhat more water-resistant than a residual insecticide, so if your dog likes to swim, the collar might be a better choice. Flea combs can be used to help remove ticks and wash your pet’s bedding frequently.

Finding and Removing Ticks

The best way to find ticks on your pet is to run your hands over the whole body. Check for ticks every time your pet comes back from an area you know is inhabited by ticks. Ticks attach most frequently around the pet’s head, ears, neck, and feet, but they are not restricted to those areas.

There are several tick removal devices on the market, but a plain set of fine-tipped tweezers will remove a tick quite effectively.

How To Remove A Tick With Tweezers

- Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Don’t twist or jerk the tick; this can cause the mouth parts to break off and remain in the skin. If this happens, remove the mouth parts with tweezers. If you can’t remove the mouth easily with clean tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal.

- After removing the tick, thoroughly clean the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol, an iodine scrub, or soap and water.

- Dispose of a live tick by submerging it in alcohol, placing it in a sealed bag/container, wrapping it tightly in tape, or flushing it down the toilet. Never crush a tick with your fingers.

Risk of disease transmission to you, while removing ticks, is low but you should wear gloves if you wish to be perfectly safe. Do not apply hot matches, petroleum jelly, turpentine, nail polish, or just rubbing alcohol alone. These methods do not remove the ticks and they are not safe for your pet. Rubbing alcohol could be used to disinfect the area before or after removing the tick.

Watch for Infection and Diseases

After you pull a tick off, there will be a local area of inflammation that could look red, crusty, or scabby. The tick’s attachment causes irritation. The site can get infected; if the pet is scratching at it, it is more apt to get infected. A mild topical antibiotic, such as over-the-counter triple antibiotic ointment, can help but usually is not necessary. The inflammation should go down within a week. If it stays crusty and inflamed longer than a week, it might have become infected.

Various diseases can be transmitted by ticks including anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, tick paralysis (or tick toxicosis), and others. Not all species of animals (pets or not) are affected similarly by every tick-borne illness.

Although ticks can transmit diseases contracted from a previous host to pets and humans, they are usually nothing more than a nuisance. The best approach is to prevent them from embedding and once embedded, to remove them quickly. If you notice your pet experiencing signs of illness or acting differently after a tick bite, it is always best to see your veterinarian. If you stay on top of the situation, your pets should cruise right through the tick season with no problems.