An Overview of Sarcoptic Mange (Scabies) in Dogs

The Organism and How It Lives

Sarcoptic mange is the name for the skin disease caused by infection with the Sarcoptes scabiei mite. Mites are not insects; instead, they are more closely related to spiders. They are microscopic and cannot be seen with the naked eye.

Adult Sarcoptes scabiei mites live three to four weeks in the host’s skin. After mating, the female burrows into the skin, depositing three to four eggs in the tunnel behind her. The eggs hatch in three to 10 days, producing larvae which, in turn, move about on the skin surface, eventually molting into their nymphal stage and finally into adults. The adults move on the skin surface where they mate, and the cycle begins again with the female burrowing and laying eggs.

Appearance

The motion of the mite in and on the skin is extremely itchy. Furthermore, burrowed mites and their eggs generate a massive allergic response in the skin that is even itchier.

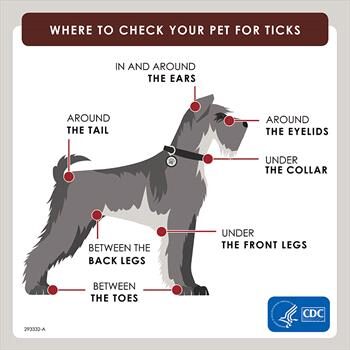

Mites prefer hairless skin, and thus, the ear flaps, elbows, and abdomen are at the highest risk for the red, scaly, itchy skin that characterizes sarcoptic mange. This pattern of itching is similar to that found with environmental allergies (atopy) as well as with food allergies. Frequently, before attempting to sort out allergies, a veterinarian will simply treat a patient for sarcoptic mange as a precaution or change to a flea product that will cover sarcoptic mange mites. This is an easy way to be sure sarcoptic mange is crossed off the list of possible skin disease causes. It is easy to be led down the wrong path and pursue allergies aggressively if sarcoptic mange is considered too unusual or unlikely.

As the infection progresses, eventually, most of the dog’s body will be involved. Classically, though, the picture begins on the ears (especially the ear margins), elbows, and abdomen.

The term scabies refers to mite infestations by either Sarcoptes scabiei or other closely related mite species. While Sarcoptes scabiei can infect humans and cats, it tends not to persist on these hosts. When people – including some veterinarians – refer to sarcoptic mange or scabies in a cat, they are usually referring to infection by Notoedres cati, a mite closely related to Sarcoptes scabiei. In these feline cases, it is more correct to refer to notoedric mange, though the treatment for both mites is largely the same.

Scabies vs. Sarcoptic Mange: Are They The Same Thing?

The term “scabies” refers to mite infections caused by Sarcoptes scabiei mites or other mites closely related to them (infections caused by the Sarcoptiform mite family). For dogs, this is usually Sarcoptes scabiei. For cats, this is usually Notoedres cati, but could be Sarcoptes scabiei. In humans, “scabies” usually refers to infection with Sarcoptes scabiei hominis, a mite that infects only people, although the canine mite discussed here (Sarcoptes scabiei) can most certainly infect people.

How The Infection is Spread

While mites can live off of a host for days to weeks depending on their life stage, they are only infective in the environment for 36 hours, which means that decontamination of the environment is generally not necessary. Spraying, deep cleaning, etc., is not necessary, although machine washing bedding is advised.

Different varieties of Sarcoptes scabei mites infest their specific mammals. Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis mites infest dogs, while Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis infests humans. Although the mites can transfer from one species to another, the infections are typically self-limiting (i.e. they go away on their own). The mites cannot complete their life cycles (they cannot reproduce and live continually) on the “wrong” hosts.

As previously discussed, when dogs are infected with Sarcoptes scabiei, those mites can transfer to people. The mites burrow into human skin, causing significant itchiness and irritation which sometimes leads to secondary skin infections (from humans scratching themselves and introducing bacteria into the skin). The mites are most active where the skin is warm, such as in bed, or where clothing is snug. Human infestations caused by dog-specific mites usually go away on their own within 12-14 days.

Always see your physician if you have concerns about your skin while your pet is experiencing a skin condition.

If a pet affected by sarcoptic mange is in the home, it is a good idea to wash any bedding in the washing machine (or replace it with new bedding) and wash any collars or harnesses.

Diagnosis

Skin Scraping

Classically, mite infection is diagnosed by scraping the skin surface with a scalpel blade and examining the skin debris under a microscope for mites. If the mite’s presence is confirmed by skin scraping, then you know immediately the cause of the itching; you need not be concerned about allergy possibilities or other diseases, and the condition can be addressed with confidence.

When an animal with sarcoptic mange scratches himself, he breaks open the tunnels that the mites have burrowed into, and the mites are killed, although the itch persists due to toxins in the skin. The result is that the mites can be difficult to confirm by skin scraping tests. (Probably mites are confirmed in 50 percent or fewer of sarcoptic mange cases.)

Medication Trial

Since negative test results do not rule out mite infection, a “maybe mange” test is frequently performed. This consists simply of treating for sarcoptic mange and observing for resolution of the signs within two to four weeks. Treatment is simple and highly successful in most cases, so it is fairly easy to rule out sarcoptic mange with a trial course of medication. See below for treatment options.

Biopsy

Mange mites are rarely seen on a skin biopsy sample, although if the sample is read by a pathologist who specializes in reading skin samples, the type of inflammation seen in the sample can be highly suggestive of sarcoptic mange. As a general rule, if the skin is biopsied, it is a good idea for the veterinarian to request that a dermatohistopathologist read the sample.

Treatment

While sarcoptic mange is difficult to diagnose definitively, it is fairly easy to treat, and a number of choices are available.

Remember, all dogs in a household where sarcoptic mange has been diagnosed should be treated.

At this point in time, many common flea products will get rid of a scabies infection handily. Using one of them will not only treat the scabies but will prevent future episodes as well. Some of these common products can be used the way they are normally used to prevent fleas, while others need an “off-label” dosing schedule that could be an issue for dogs with the MDR1 mutation.

Some individuals have a mutation of the MDR1 gene that interferes with the dog’s ability to metabolize many drugs, including those related to ivermectin, a broad-spectrum antiparasitic. This is not an issue at label doses but can be really toxic at the doses used to kill mites. These individuals are usually of the Collie family: Collies, Shetland Sheepdogs, and Australian Shepherds are classically affected. There is now a DNA test that can determine if any dog has the mutation. If there is any question, a medication that does not require an off-label dose adjustment should be used for mange treatment.

The Isoxazolines

Oral flea products that cover both fleas and ticks are popular and include Nexgard®, Simparica®, Bravecto®, and Credelio®. Any of these will readily kill sarcoptic mange mites in one dose just as readily as they handle fleas and ticks. The MDR1 mutation does not come into play.

Selamectin (Selarid® or Revolution®)

Selamectin is an ivermectin derivative for dogs to control fleas, ticks, heartworm, ear mites, and sarcoptic mange mites. Normal monthly use of this product should prevent a sarcoptic mange problem, but to clear an actual infection, an extra dose is usually needed after 2 weeks for reliable results. This extra dose could possibly be an issue for dogs with the MDR1 mutation.

Moxidectin (Advantage Multi) – Moxidectin is yet another ivermectin derivative. In Advantage Multi, it is combined with imidacloprid, a flea-killing topical, to create a product used against heartworm, hookworm, roundworm, whipworm, and fleas. In the U.S., this product is now FDA labeled for sarcoptic mange and is also a good choice where there is concern about the MDR1 gene mutation as one regular dose should handle the mange mites.

Milbemycin Oxime (Interceptor®, Sentinel®, or Trifexis®)

Milbemycin oxime is approved for heartworm prevention as a monthly oral treatment and is available combined with oral flea products as well. Happily, it also has activity against sarcoptic mange, and several protocols have been recommended. There could be issues with the MDR1 mutation, depending on the protocol.

Ivermectin

This is one of the most effective treatments against Sarcoptes scabei yet is off-label as far as the FDA is concerned. There are several protocols due to its long activity in the body. Typically, an injection is given either weekly or every two weeks in 1-4 doses. Because there are so many safer and more convenient derivatives at this point, we mostly mention it for its historical significance because, before its development, mange treatment was labor intensive with repeated dipping and bathing. Ivermectin opened the door for a simple treatment for this condition.

Dipping

Here, a mite-killing dip is applied, usually following a therapeutic shampoo. Weekly mitaban dips (Amitraz), or lime-sulfur dips are usually effective. The disease typically resolves within one month. Dipping is troublesome, messy, and rarely done anymore as the other products are easier and more rapidly effective. We only mention it since it had been a standard mange treatment for decades prior to ivermectin.

In the Meantime

During the time it takes to control the mite infection, the pet will be very itchy. Controlling secondary bacterial infections with antibiotics is important. Also, since the body’s reaction to the mite is one of hypersensitivity (essentially an allergic reaction), a cortisone derivative is worthwhile to quell the itchiest symptoms. Ask your veterinarian about which prescriptions are appropriate for your pet. As for anti-itch shampoos, rinses, and other forms of itch relief, see itch-relieving ideas for additional suggestions.