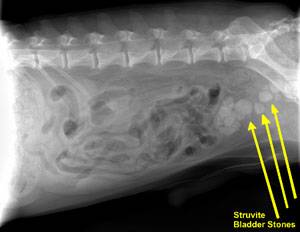

Bladder Stones (Struvite) in Dogs

There are many types of bladder stones, and each type forms under specific circumstances. In almost all cases, struvite bladder stones in dogs are caused by bladder infection with specially enabled bacteria. Staphylococci (often simply called Staph) and Proteus bacteria are the usual culprits, and they gain access to the bladder by simply crawling up from the lower urinary tract.

- 85% of patients with struvite bladder stones are female.

- Breeds felt to have an increased risk for the formation of struvite stones are the Miniature Schnauzer, Shih Tzu, Yorkshire terrier, Labrador retriever, and Dachshund.

The average age of patients with struvite bladder stones is 2.9 years.

Some patients with bladder stones show no symptoms of any kind and the stones are discovered incidentally but there are some symptoms that might promote a search for stones. Bloody urine, recurrent bladder infection (especially by the same organism and especially if Staphylococci or Proteus is cultured), or straining to urinate all would raise suspicion. Fortunately, struvite stones are radio-opaque, which means they show up readily on radiographs.

Occasionally stones are simply passed and discovered by the pet owner. If this occurs, it is important to bring the stone to your vet’s office for analysis, have the dog examined, and have radiographs taken to check for more stones. Patient care will be highly dependent on the stone’s mineral composition.

When to Suspect Struvite Stones

Bladder stones come in several mineral compositions. The most common stone types are oxalate and struvite. Since the approach is different for each type, it is crucial to determine the stone type. The stone type can be confirmed if a sample stone is available (either passed naturally or obtained via surgery, voiding urohydropropulsion, or cystoscopy). A laboratory analysis can easily determine the content of the stone and even determine if the stone consists of layers of different mineral types. Without a sample stone, there are still some hints that can be obtained through other tests.

As mentioned, struvite stones in dogs are almost always formed because of the urinary changes that occur with specific types of bladder infection: almost always Staphylococcal infection but occasionally a Proteus infection. If a urine culture from a patient with a bladder stone should grow either staph or proteus, this would make struvite more likely than oxalate. Also, struvite requires an alkaline pH to form while oxalate requires an acid pH to form; urine pH is a part of any urinalysis and thus provides another clue as to the stone’s identity.

An educated guess is better than nothing but does not replace the analysis of a stone. Remember, occasionally a stone of one type forms around a stone of another type. A complete analysis is needed to effectively prevent a recurrence.

How Do Struvite Stones Form?

Struvite is the name given to the crystal composed of magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate. (Struvite is also occasionally referred to as “triple phosphate” due to an old erroneous belief that the phosphate ion was bonded to three positive ions instead of just magnesium and ammonium.) Struvite crystals are not unusual in normal urine, and their presence alone does not require treatment. Combine them with certain bacteria, however, and a stone is created.

Stone creation is made possible by an enzyme called urease that certain bacteria, particularly Staphylococci and Proteus species, can produce. Urea is a substance seen in large amounts in urine. Where does all this urea come from? In short, when the body breaks down amino acids, it must contend with the ammonium that is generated in this process. The ammonium, which would be toxic if left alone, is converted to urea, which is much less toxic and is readily soluble in water, making for its easy disposal in urine. Unfortunately, adding urease-positive bacteria into the urinary bladder converts the urea back into ammonium. The combination of infection and inflammation caused by the ammonium creates a matrix that traps the struvite crystals and gels into an actual stone. This reaction can only take place in alkaline urine but the ammonium creates the perfect pH for stone formation. In dogs, the general rule is, if there is no infection, there are no struvite bladder stones.

There are a few rare exceptions to this rule. Certain antacids and diuretics can produce struvite stones when there isn’t any infection. A hormone imbalance called hyperaldosteronism is associated with struvite stone development. The hereditary situation of the English cocker spaniel also represents an exception, as in at least one genetic line of this breed has the tendency to form a purely metabolic struvite stone has been documented. These situations are rare, and for most patients, the focus of struvite stone management is dealing with bladder infections and preventing future ones.

What Should Be Done About Struvite Bladder Stones?

Struvite stones can be removed surgically with a technique called voiding urohydropropulsion; removed with a cystoscope (if they are small enough); or dissolved by diet (also called dissolution). Stone dissolution with diet is the least invasive and probably the best option unless the patient really needs a faster treatment, such as if there is a risk of urinary obstruction in a male dog. Each approach has pros and cons.

Dietary therapy to prevent new struvite stones is of secondary importance in dogs (except the English Cocker spaniel, for which this is a hereditary metabolic problem rather than a matter of infection).

The English Cocker Spaniel has a unique genetic predisposition to make struvite stones even without any infection. Image courtesy of David Gjestson.

The focus is on preventing infection. If your dog has a history of struvite bladder stones, be sure to discuss long-term monitoring and understand what schedule of testing is best for your pet. Expect periodic urine cultures to be needed.

Dietary Dissolution

Dietary dissolution of the stone is not only possible with struvite bladder stones, it is actually the treatment of choice. There are several therapeutic diets available by prescription from your veterinarian that are designed to dissolve struvite bladder stones when they are in the bladder by creating urine that is not compatible with the solid state of struvite.

A therapeutic diet must be the only food fed until the stone is dissolved. Antibiotics are needed as long as stones are in the bladder (bacteria are encrusted within the stone and as the stone dissolves, they are released). Every 4 to 6 weeks, new radiographs are taken to evaluate the stone size. If it is at least 20 percent smaller, the process is continued. A urinalysis is also checked to be sure the proper urinary conditions for dissolution are being created by the diet.

On average, 2 to 3 months are needed to dissolve stones, but the diet should be continued for a full month after the stones are no longer visible on radiographs because small stones may not be large enough to see. Small stones are typically dissolved in just a few weeks as long as the infection is controlled.

After the stones are dissolved, periodic (usually quarterly) urine cultures are performed to check for infection recurrence. If stones do not shrink as expected on the dissolution diet, they may not be pure struvite stones, and another method described below should be selected.

The main advantage of the dissolution method is that it seems to be the lowest risk and most comfortable approach for the dog. That said, an important disadvantage of the dissolution approach is the possibility of urinary tract obstruction as the stone gets smaller and gets lodged in the urethra on the way out. This is potentially a life-threatening hazard for male dogs as they have a narrow urethra. The stone cannot be dissolved in the urethra as, for dissolution to work, the stone must be immersed in urine, which is not the case in the urethra. Furthermore, the inability to pass urine is an emergency, and the patient will die of uremic poisoning in a matter of days if urine flow cannot be restored. The stone can be pushed back into the bladder and dissolution re-attempted but at this point, it may be best to go for a faster resolution with surgery, lithotripsy, cystoscopy, or voiding urohydropropulsion.

Many dissolution diets are really high in fat and high in salt. They may not be appropriate for patients with a past or current history of pancreatitis, patients with heart disease, kidney insufficiency, or high blood pressure.

Surgery

Surgical removal is the most direct method. The advantage is that the stones are removed and healing may commence all in one day. The chief disadvantages are those inherent to surgery: anesthetic risks, post-operative pain, risk of contaminating the abdomen with infected urine, the possibility that not all stones will be removed, and the possibility that the bladder stitches will not properly hold. These risks are generally considered minor and complications associated with cystotomy (opening of the urinary bladder) are unusual. The patient usually stays in the hospital for a day or two to be sure urine production is normal, to properly confine the patient, and to assess pain.

If the dog has urethral stones, they can usually be flushed back into the urinary bladder for surgical removal. If the stone is lodged too tightly for this, it can be removed surgically from the urethra, although the potential for urethral scarring usually makes this a last-choice approach.

Voiding Urohydropropulsion

If the stones are small enough to pass, the bladder can be manipulated in a way to promote expelling them through the urethra. This is called voiding urohydropropulsion and involves filling the bladder, agitating it so the stones float freely in the urine, and then generating a high-pressure urine stream to force the stones out. The patient must typically be held vertically so that gravity may assist in the expulsion of the stones. This technique only works if the stones are small and the patient is not too large. Sedation or general anesthesia is needed. If there are numerous stones, several attempts are often needed if this is to be the only means of removal. Often, this technique is used to obtain a sample stone for analysis to determine if dietary dissolution is feasible.

Cystoscopic Retrieval/Laser Lithotripsy

If you wish to avoid surgery and the stones are small enough, a cystoscope can be passed into the patient’s bladder, and the stones retrieved with a basket (or fragmented via laser lithotripsy). This requires specific equipment most clinics do not have, and thus, usually needs referral to a specialty practice. It is generally more expensive than surgery, though recovery time for the patient is typically much faster.

Recurrence

After stones are removed one way or another, the focus shifts to prevention. Often, patients are somehow predisposed to a bladder infection, which means they are also predisposed to form more struvite bladder stones. A stone can form as quickly as two weeks after infection if a urease-positive bacterium sets in.

After surgery, antibiotics must be continued until the infection is confirmed to have cleared (i.e., a negative urine culture is obtained). After this, a follow-up schedule of radiographs and/or urine testing is recommended. For a single stone episode, only a few follow-up visits may be necessary. Realize that some individual animals are predisposed to recurring bladder infections, and they may form new struvite stones repeatedly. Obviously, if stones were to recur, a more regular monitoring schedule would have to be revised.

Dietary therapy in the prevention of struvite stones is of secondary importance in dogs (with the exceptions being the rare situations mentioned above). The focus is on preventing infection. If your dog has had a history of struvite bladder stones, be sure to discuss long-term monitoring and understand what testing schedule is best for your pet. Expect periodic urine cultures to be needed.