The normal lens of the eye is a focusing device. It is completely clear and is suspended in position by tissue fibers (called zonules) just inside the pupil. The pupil opens and closes to control the light entering the eye so as to project an image onto the retina in the back of the eye, the way a projector projects an image onto a movie screen. The lens focuses the projected image in a process called accommodation. The focusing power of the dog’s lens is at least three times weaker than that of a human lens, while a cat’s lens is at best half the power of a human’s.

(Dogs and cats have a sense of smell at least 1,000 times more accurate than ours and this is their primary means of perceiving the world.)

Anatomy First

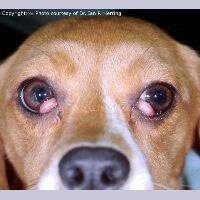

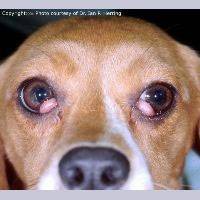

Despite its clarity, the lens is in fact made of tissue fibers. As the animal ages, the lens cannot change its size and grow larger; instead, it becomes more compact with fibers. The older lens, being denser, appears cloudy. This condition is called nuclear sclerosis and is responsible for the cloudy-eyed appearance of older dogs. The lenses with nuclear sclerosis may look cloudy but they are still clear and the dog can still see through them; these are not cataracts.

The fibers making up the lens come together in the center of the lens, forming a “Y” shape that is sometimes visible when one looks into the eye. These Y-shaped lines are often called the sutures of the lens.

The lens is enclosed in a capsule that, if disrupted, allows the immune system to see the lens proteins for the first time, recognize them as foreign, and attack. The resulting inflammation (a form of uveitis) is painful and can be damaging to the eye. A cataract can result from this inflammation or from any of the numerous other reasons listed below.

A cataract is an opacity in the lens.

A Note on Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs

Cataracts can be congenital (born with it), age-related; of genetic origin (the most common cause); caused by trauma; dietary deficiency (some kitten milk replacement formulas have been implicated); electric shock; or toxins. The patient with a cataract is not able to see through the opacity. If the entire lens is involved, the eye will be blind.

Many things can cause the lens to develop a cataract. One cause is diabetes mellitus. In this condition, the blood sugar soars as does the sugar level of the eye fluids. The fluid of the eye’s anterior chamber is the fluid that normally nurtures the lens but there is only so much glucose that the lens is able to consume. The excess sugar is absorbed by the lens and transformed into sorbitol. Sorbitol within the lens unfortunately draws water into the lens, causing an irreversible cataract in each eye. Cataracts are virtually unavoidable in diabetic dogs no matter how good the insulin regulation is; diabetic cats have alternative sugar metabolism in the eye and do not get cataracts from diabetes.

What Else Could It Be?

Many owners cannot tell which portion of the eye looks cloudy. Cloudiness on the cornea, as caused by other eye diseases, can be mistaken for a cataract by an inexperienced owner. Also, in dogs, the lens will become cloudy with age as more and more fibers are laid down, as described above. Nuclear sclerosis, as described, can mimic the appearance of a cataract, yet the eye with this condition can see and is not diseased. It is a good idea to have your veterinarian examine your pet if you think there is a cataract, as you could be mistaken.

Why is it Bad to Have a Cataract?

The area of the lens involved by the cataract amounts to a spot that the patient cannot see through. If the cataract involves too much of the lens, the animal may be blind in that eye and there could be cataracts in both eyes, which means the pet could be rendered completely blind.

A cataract can luxate, which means that it can slip from the tissue strands that hold it in place. The cataractous lens can thus end up floating around in the eye, where it can cause damage. If it settles to block the eye’s natural fluid drainage, glaucoma (a buildup in eye pressure) can result, leading to pain and permanent blindness. A cataract can also cause glaucoma when it absorbs fluid and swells so as to partially obstruct fluid drainage.

Cataracts can begin to dissolve after they have been there long enough. While this sounds like it could be a good thing, in fact, it is a highly inflammatory process. The deep inflammation in the eye creates a condition called uveitis, which is in itself painful and can lead to glaucoma. If there is any sign of this type of inflammation in the eye, it must be controlled before any cataract surgery.

A small cataract that does not restrict vision is probably not significant. A more complete cataract may warrant treatment. Cataracts have different behavior depending on their origin. If a cataract is a type that can be expected to progress rapidly (such as the hereditary cataracts of young cocker spaniels) it may be beneficial to pursue treatment (i.e. surgical removal) when the cataract is smaller and softer, as surgery will be easier.

What Treatment is Available?

Cataract treatment generally involves surgical removal or physical dissolution of the cataract under anesthesia. This is invasive and expensive and is not considered unless it can restore vision or resolve pain. Pets with one normal eye and the other with a cataract can still see with their good eye and may not need surgery depending on circumstances.

Determining if a Dog is a Candidate for Cataract Removal

Obviously, the patient must be in good general health to undergo surgery; diabetic dogs must be well-regulated before cataract surgery. Also, it should be obvious that for a patient to be a good candidate for surgery, the patient must have a temperament conducive to getting eye drops at home.

Pre-anesthetic lab work can be done with the patient’s regular veterinarian. Some ophthalmologists prefer that patients have their teeth cleaned before surgery to minimize infection sources in the eye.

A complete examination of the eye should be performed. If your veterinarian is not comfortable treating cataracts or does not have the appropriate equipment, your pet may be referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist.

It is impossible to see the retina through a cataract; an electroretinogram test can determine if the eye has a functional retina and can benefit from cataract surgery. Ultrasound of the eye can be used to look for retinal detachments. If the eye has a blinded retina, there is no point in subjecting the patient to surgery. Inflammation in the eye will require treatment before surgery. Sometimes, other eye drops are prescribed for a period before surgery depending on the veterinarian’s preference.

Cataract Removal: Phacoemulsification and Surgical Removal

Historically, removing the cataract meant surgically cutting into the eye and physically removing the lens. This is still done for older patients whose lenses are compact. For younger patients in whom the lens is soft, a technique called phacoemulsification is preferred.

This technique has become the most common method of removing cataracts in dogs. Here, the lens is broken apart by sound waves and removed with an instrument similar to a small vacuum cleaner.

In either case, the eye must be paralyzed during surgery to prevent eye movement or even blinking at a critical moment. Nerve blocks can be used to paralyze the eye, or specific medications can be used to paralyze the entire patient (in which case a mechanical ventilator is used to breathe for the patient during surgery). After the lens is removed, an artificial lens is implanted. (Without the prosthesis, the dog’s vision will be approximately 20/800, and objects will appear to be reversed, as in a mirror.)

After surgery, the pet must wear an Elizabethan collar for a good three weeks, and eye drops to reduce inflammation will be needed for several months. A harness may be recommended for walks instead of a collar to reduce pressure on the head and eye from pulling. There will be a schedule of recheck appointments.

Complications

Some degree of uveitis (deep inflammation) is unavoidable. This can cause a pupil constriction reaction that can increase the risk of scarring within the eye. Eye drops to keep the pupil dilated are usually effective in preventing this but not always. Inflammation in the eye will resolve over weeks to months after surgery. The success rate is higher for cataract surgery if there is minimal inflammation in the eye prior to surgery, thus pre-operative anti-inflammatory eye drops are frequently prescribed.

Another complication involves the development of opacities on the remaining lens capsule. In humans, laser surgery is used to remove the lens capsule, but in dogs, the capsule is too thick for this. Some ophthalmologists prefer to remove the capsule as a preventive measure. The portion of the capsule that is involved in this reaction is present in young dogs but not in adult dogs.

Bleeding after surgery can be an enormous complication and can easily be caused by excess barking or activity after surgery. Small bleeds are of little consequence, but a large bleed could ruin vision.

Glaucoma can develop at any time after cataract surgery. This complication is not only blinding but painful as well. The risk of this complication has been decreased by placing a prosthetic lens (a formerly uncommon but now fairly standard procedure) but dogs who start off with hypermature (dissolving) cataracts or have an unusually long surgery time tend to have an increased risk for this complication.

Overall, a 95 percent vision rate is described immediately after cataract surgery with 80 percent having long-term vision success.

Before embarking on the adventure of cataract surgery, be sure to obtain a clear explanation from your veterinarian or ophthalmologist of exactly what the home care will involve.

What if the Cataract Goes Untreated?

A cataract by itself does not necessarily require treatment. If there is no associated inflammation or glaucoma and the only problem is blindness, it is perfectly reasonable to have a blind pet. Blind animals have good life quality and do well though it is important not to move furniture around or leave any hazardous clutter in the home. Some dogs, however, become anxious or even aggressive when they lose their vision. Restoring vision for the pet is weighed against risk and expense and is a decision for each owner to make individually. Many cataracts will progress to a hypermature state where they will begin to dissolve as described and anti-inflammatory eye drops are needed as mentioned.

Can Eye Drops Dissolve Cataracts?

Products containing N-acetylcarnosine have been marketed to dissolve cataracts and have led to a great deal of false hope. N-acetylcarnosine is an antioxidant eye drop that may have beneficial effects on the eye but they do not include any sort of dissolution of a mature cataract. For smaller cataracts, it may be possible to dilate the pupil so that the pet can see around the cataract but there is some controversy about doing so as these medications have other effects on the eye.