Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is one of the more common acquired heart diseases in dogs. DCM is a primary disease of the heart muscle (cardio = heart; myo = muscle; pathy = disease) in which the heart muscle (myocardium) of the lower pumping chambers (ventricles) becomes weak and so loses its ability to contract normally. DCM most commonly affects the left side of the heart (the side that receives blood from the lungs and pumps it to the body), specifically the left ventricle.

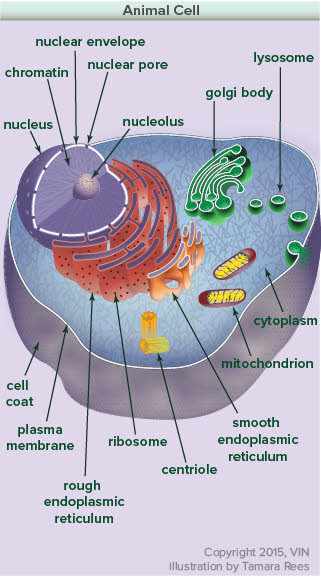

Graphic by Tamara Rees of VIN

When the myocardium cannot pump blood out of the left heart effectively, the kidneys retain sodium and water to increase the amount of blood returning to the heart. This leads to an enlargement of the ventricles in order to compensate for the ineffective pumping. This is helpful for years, but ultimately becomes detrimental when it causes the blood pressure in the heart to back up into the lungs, thereby causing fluid accumulation within the lungs (pulmonary edema). This is called heart failure or congestive heart failure (CHF).

Although less common, DCM affecting the right ventricle can also occur. Blood backs up on the right side, which receives blood from the body and pumps it to the lungs, resulting in right-sided CHF, where fluid accumulates in the abdomen (ascites) and chest (pleural effusion). DCM affecting the right ventricle is almost always accompanied by DCM of the left ventricle.

What Breeds get DCM?

There are several breeds that are predisposed to DCM. These include Doberman Pinschers, Great Danes, Irish Wolfhounds, Boxers, Newfoundlands, Portuguese Water Dogs, Dalmatians and Cocker Spaniels. DCM is not just limited to specific breeds. Large and giant breeds are most commonly affected, but it also occurs in smaller breed dogs and cats as well.

The causes of DCM in these breeds vary, as explained below.

What Causes DCM?

Because of the strong breed association, DCM almost certainly is inherited in many breeds. Genetic mutations that are associated with DCM have been identified in Doberman Pinschers, Boxers and Standard Schnauzers. Genetic testing for these mutations can be done for each.

Boxers get a specific type of cardiomyopathy called arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). Approximately 90% of these dogs in the USA have a ventricular arrhythmia and an otherwise normally functioning heart. They are prone to fainting and sudden death. The fainting most commonly happens when they develop a very fast heart rate (greater than 400 beats/min). Sudden death usually occurs when this fast rate degenerates into ventricular fibrillation (cardiac arrest). Approximately 10 percent also get DCM as a part of their disease. The disease is associated with a genetic mutation in a gene called striatin.

In some dogs, DCM is due to a nutritional deficiency. Taurine is an amino acid required for the development and function of the myocardium. Consequently, pets may develop DCM on taurine-deficient diets, such as vegetarian diets, and may benefit from appropriate supplementation. Some breeds, such as American Cocker Spaniels and Golden Retrievers, may have a predisposition to taurine-deficiency, possibly through defects in metabolizing taurine. Many, but not all, cases that are supplemented with taurine will improve. Some also need carnitine supplementation. If your pet is diagnosed with DCM, testing for a taurine deficiency may be warranted. Breeds such as Doberman Pinschers and Great Danes do not have taurine-deficient cardiomyopathy. Some cats may develop taurine-deficient DCM, although this has become rare as taurine is now added to virtually all quality cat foods (see Feline Cardiomyopathy).

L-carnitine is another amino acid that has rarely been implicated in the development of DCM in people. L-carnitine is required for the myocardial cells to produce energy and thus contract. There is some evidence that a deficiency in this molecule will contribute to myocardial dysfunction in Boxers (one small study only). Some American cocker spaniels need to be supplemented with it, along with taurine, to produce a beneficial response. However, the role of carnitine in most DCM cases is very limited.

In 2018, grain free diets were implicated in causing DCM in dogs, especially in breeds that do not typically get DCM. Read more details about this potential cause.

Occasionally, toxins can cause DCM. The most common toxin is doxorubicin (Adriamycin), an anti-cancer drug used to treat various cancers in dogs. In some cases, dogs receiving doxorubicin will develop DCM.

Infectious causes of DCM are rare. Puppies infected with parvovirus at two to four weeks of age can develop DCM. These days, vaccinating the mother protects the puppies against parvovirus during this susceptible period, so this cause of DCM is rarely seen. Chagas disease (Trypanosomiasis) can cause DCM in geographic areas where it is found (Texas, Mexico).

What are the Signs of DCM?

Signs of DCM vary depending on the breed of dog and stage of the disease. Loss of appetite, pale gums, increased heart rate, coughing, difficulty breathing, periods of weakness, and fainting are signs commonly seen. Since blood is backed up into the lungs, respiratory signs (CHF) due to pulmonary edema are most common. Blood returning to the right side of the heart from the body may also back up leading to fluid accumulation in the abdomen (ascites) or in the chest cavity (pleural effusion). Weakness or collapse may be caused by abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias) and occasionally, decreased blood flow to the body (depressed cardiac output).

In some breeds, sudden death or fainting can occur well before any signs of CHF.

How is DCM Diagnosed?

There are two different methods used to diagnose pets: (A) during a screening exam of an apparently normal dog (e.g. as part of a breeding program), and (B) during examination of a dog with clinical signs of heart disease.

Screening Exams for DCM

Many conscientious breeders and owners of dogs that are predisposed to DCM screen their pets for heart disease to try to minimize the risk of transmitting the disease to offspring. Screening for DCM in dogs can be expensive and complex. The screening test of choice depends on the breed of the dog and the stage of the disease.

The first step is a good physical examination. In most cases, the physical examination is completely normal. Occasionally, the veterinarian may detect an arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm). In Doberman Pinschers and Boxers, a 24-hour ECG recording using a 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitor (Holter monitor) is often the best way to screen dogs for early signs of DCM since an abnormal rhythm often occurs before any detectable changes in myocardial contractility. An echocardiogram (an ultrasound scan of the heart) is also used to identify dogs with DCM before they develop clinical signs, but many dogs with mild disease have equivocal findings. This examination is best performed by a board certified veterinary cardiologist.

Genetic testing should be done by breeders of the specific breeds where a mutation or mutations have been identified.

Diagnosis in Dogs with Clinical Signs

A thorough physical examination by your veterinarian, coupled with your pet’s clinical signs and specific breed, may help make the presumptive diagnosis of DCM. Tests that help support the diagnosis are an ECG (electrocardiogram) and x-rays (radiographs) of the chest. The ECG may show an arrhythmia and/or an elevated heart rate. The chest radiographs may show an enlarged heart and/or fluid in the lung tissue or chest cavity. Some dogs may have normal chest radiographs, but have arrhythmias on their ECG. These pets may be in the early stages of DCM (see above).

In dogs with clinical signs of heart failure, an echocardiogram is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of DCM. With an echocardiogram, a cardiologist can visualize the heart and assess its function. A decrease in heart pumping function (contraction) means that the patient has DCM. Your veterinarian may also perform blood tests to look for any underlying nutritional or infectious conditions if the specific case warrants such investigation.

How is DCM Treated?

Treatment of heart failure is based each individual patient. Drugs commonly used are diuretics (most commonly furosemide), ACE inhibitors, and pimobendan. The diuretic forces the kidneys to excrete more sodium and water. It is used to eliminate pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs) and so improve breathing and/or effusion (fluid accumulation in the chest or abdominal cavities). Pimobendan increases the force of contraction of the ventricles and dilates blood vessels. Both furosemide and pimobendan are effective treatments that prolong survival and improve quality of life.

Pimobendan might increase the time until onset of heart failure in Doberman Pinschers with DCM when given prior to the onset of heart failure.

Management of arrhythmias is often an important part of managing DCM. Dogs with atrial fibrillation are most commonly treated with a combination of digoxin and diltiazem in order to reduce the heart rate. Sotalol alone or in combination with other antiarrhythmic drugs is used in Boxers and in some Doberman Pinschers to suppress ventricular premature complexes and tachycardia in order to stop the dog from fainting and from dying suddenly. Mexiletine is also commonly used in Doberman Pinschers.

In nutritional DCM, specific supplements will be prescribed. Patients with right-sided heart failure will also have fluid physically removed from the abdomen and/or chest cavity by the veterinarian to make the patient more comfortable.

In humans, DCM patients usually get heart transplants. However, this option does not exist for veterinary patients. Other surgical procedures have been evaluated, but currently none are being offered for patient care.

What is the Prognosis of a Pet Diagnosed with DCM?

Unfortunately, in most cases DCM is a progressive, irreversible, and ultimately fatal disease. Survival depends on the stage of disease, the breed of the patient, the specific type of DCM that patient has, and patient/owner treatment compliance. In taurine-deficient DCM, correcting the deficiency in cats results in complete cure. In dogs, correcting the deficiency may result in at least partial reversal of the disease and prolonged survival; however, some cases relapse after several years.

DCM is a slowly progressive disease. If it is diagnosed in the early stages, the patient may live several years before developing clinical signs. In some breeds, such as Doberman Pinschers, sudden death accounts for 30 percent of the deaths from DCM, well before these dogs ever develop CHF.

In other breeds with DCM, such as Doberman Pinschers and Great Danes, in dogs showing clinical signs of CHF medical therapy can help prolong survival. Historical average survival for Doberman Pinschers with clinical DCM was two to three months. However, with pimobendan, recent studies have seen extended survival for this breed to one year. Less is known about outcomes of other breeds with DCM. Once the diagnosis of DCM is made, ask your veterinarian to discuss your pet’s prognosis on an individual basis.

Can I do Anything to Prevent DCM or Slow its Progression?

Currently, the primary intervention that has been shown to alter the course of DCM is nutritional supplementation in dogs with a nutritional deficiency (i.e., taurine deficiency). Since the majority of cases are thought to be genetic, breeding from lines unaffected by the disease helps reduce the chance of inheriting DCM. Genetic tests, when they are available, are of value in determining breeding strategies. In Doberman Pinschers, pimobendan has been reported to prolong a composite survival endpoint although it did not prolong the time until the onset of heart failure and did not prolong the time until sudden death.

What about Other Supplements?

Multivitamin supplements, nutritional supplements, Co-enzyme Q10, and non-Western herbal supplements have all been used for DCM, but none have been examined critically to determine if they hurt or help patients. Use of these supplements is best discussed with your veterinarian.