Blastomycosis is a Systemic Fungal infection Affecting Dogs and Cats

Blastomycosis, caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, is a systemic fungal infection that affects dogs and cats. Blastomycosis is most common in certain geographic areas in North America, most often the Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, Tennessee, and St. Lawrence River valleys, and in three provinces of Canada (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba). It has also been reported in Africa, India, Europe, and Central America. (Fungal growth is supported by wet, sandy, acidic soils rich in organic matter, which is why it is found in valleys and is seen most frequently near water.)

Pathophysiology

Infection with Blastomyces occurs when a cat or dog inhales the fungal spores into the lungs. The incubation period is from 5 to 12 weeks. Some animals don’t show clinical signs for a long time after being infected, but those animals are not contagious to other animals and people. Blastomycosis organisms have a predilection for the respiratory tract, and pulmonary disease is the most common sign (88-94% of canine cases). Once the lung disease develops, yeast forms of the organism spread throughout the body. Organs typically affected include eyes, bones, skin, lymph nodes, subcutaneous tissues, brain, and testes. It can also be found in the nose, prostate, liver, mammary glands, and heart, but those locations are less common.

Dogs appear to be much more susceptible to infection than other species. Although the disease does occur in both people and cats, the incidence is much lower than in dogs. Dogs are ten times more likely to contract the disease than are people, and 100 times more likely than are cats. The incubation period in dogs is also shorter than in people. The reason dogs are more susceptible is unknown, but immune-deficiency may play a role. Annual prevalence in dogs in endemic areas is estimated at 1-2%. Many infected animals live within 0.25 mile of water. An increased number of cases can occur after periods of unusually heavy rainfall. Historically, young (i.e. 1-5 years), male, large-breed (e.g. hounds, pointers) dogs have had the highest risk of infection. (This is probably because these animals would tend to have more contact, due to hunting activities, with the organism’s geographical area.) However, any age, breed, or sex of dog can be infected.

Clinical Signs

The signs of illness will depend on what organs are infected. Some dogs will have eye problems, and some will have neurological signs (seizures, head tilt, etc.). Lameness may occur, if the infection is in the bones. Owners of dogs in the specific geographic areas should watch for coughing, difficulty breathing, eye inflammation, enlarged testicles, fever, swollen lymph nodes, ulcerated/draining skin lesions, bloody urine, difficulty urinating, nasal cavity signs (including bloody nasal discharge), and lack of appetite. (Weight loss occurs because of the decreased appetite.) Infections in the nasal passages may result in skull damage, and lead to infection of the brain. Large skin abscesses and neurologic signs are more common in cats than in dogs, while bone lesions are more common in dogs than in cats. Hypercalcemia can occur in dogs, although it’s rare in cats and non-domestic feline species.

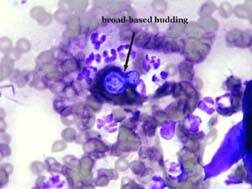

Diagnosis

Diagnosis involves physical exam, blood tests, imaging (radiography, ultrasonography, CT, etc.), urinalysis to look for Blastomyces yeast, cultures, serology, and biopsies of affected organs. Fungal serology, to look for antibodies, is not always accurate and has been known to produce false negatives. The enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for B. dermatitidis galactomannan antigen appears to have a high sensitivity in urine (93.5%) and serum (87%). The EIA assay is commercially available; cross reactions with Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, and Penicillium marneffei can occur with this assay. The definitive diagnosis is finding the fungus in the tissues.

Treatment

Treatment involves various antifungal medications, including itraconazole, ketoconazole, fluconazole, amphotericin B, and some combination therapies. These medications usually need to be taken for a long period of time; how long depends on the specific case. Treatment usually can be done at home, unless the disease is severe. Pets with respiratory involvement should be on restricted activity. In severely ill dogs, intravenous fluids, oxygen, antibiotics for secondary infections, and pain medication may be necessary. Skin lesions may require wound cleaning and debridement.

Eyes that are severely affected may not respond well to the treatment because the medication does not penetrate eyes very well. Ocular blastomycosis cases may need systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy, topical anti-glaucoma medications, etc. Significantly affected eyes may require enucleation (removal of the eyeball).

Pets with severe lung disease may get worse at the beginning of treatment because the fungal organisms are dying; the mass death of organisms can cause severe respiratory problems.

Patients may not appear to improve for one to two weeks after the start of treatment. Close monitoring should be done for the first two weeks, and then rechecks are usually scheduled on a monthly basis. Rechecks may involve blood tests, biochemistry profiles, and imaging, if appropriate.

Prognosis

The prognosis for many pets is good, especially if owners can afford to treat the pet for long enough. Approximately 50% to 75% of affected dogs recover when treated with itraconazole, fluconazole, or an amphotericin-ketoconazole combination. Prognosis is poor for dogs with severely affected lungs, but if the dog survives the first 7 to 10 days of therapy, the prognosis improves. However, mortality rates in dogs with Blastomyces dermatitidis can be as high as 41%.

The prognosis for the retention of vision, in animals that have eye disease, is variable.

Dogs with brain involvement often die. Seizures are common upon death of the organism and may be uncontrollable.

Prognosis is also poor when at least 3 body systems are involved.

Relapses are most likely to occur in dogs that had a severe case at onset, or dogs that were not treated long enough. Relapses are most common within the first 6 months after treatment. Dogs that recover from the disease are probably not immune to getting it again.

After discontinuing therapy, animals may be rechecked at 1, 3, and 6 months for evidence of relapse. In one study, relapse rates for itraconazole and fluconazole were 18% and 22%, respectively. Relapses are treated like a new infection.

There is no way to prevent your pets’ exposure to Blastomyces other than by keeping them away from affected geographic areas.

Zoonotic Potential

Blastomycosis is not considered to be a zoonotic disease. It is acquired by humans via inhalation or direct contact with infective conidia/spores. Risk of infection is higher for excavation workers, and for people working or playing in wooded areas with waterways. Blastomycosis cannot be spread between dogs and other animals, or between dogs and people. However, immunocompromised people should limit their contact with infected pets and should wear gloves when cleaning and treating draining lesions.