Fibrocartilaginous Embolism (FCE) in Dogs

Imagine your dog is happily playing in the yard, jumps up to catch a ball, lands badly, and comes up not just lame but weak or even paralyzed in a back leg. Possibly both back legs. The toes of the affected foot may knuckle under. Maybe his back tilts downward, his rear legs too weak to rise all the way up. You check him over, trying to find where it hurts, and it simply does not seem to hurt at all.

There are many conditions that might fit here, but the neurologic knuckling and the absence of a tender spot suggest a fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE).

What is FCE, Anyway?

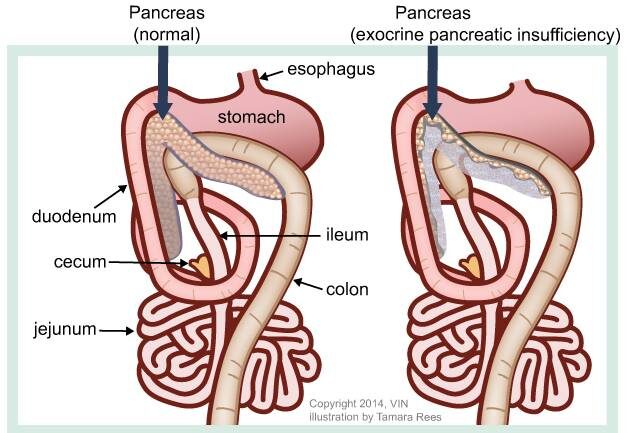

To understand FCE (fibrocartilaginous embolism), one has to understand some anatomy of the vertebral column. The vertebral column consists of numerous small bones called vertebrae that are linked together by joints called intervertebral disks. The disks are similar to the joints that connect arm or leg bones together in many ways. They allow flexibility between vertebrae so that you can arch or twist your back voluntarily, just as you can flex and extend a knee or elbow.

The disks are unique as well. A joint of the appendicular skeleton, say a knee or elbow, has a capsule that secretes a lubricating fluid. The bones are capped with smooth cartilage to facilitate frictionless gliding as the surfaces move during flexion and extension. The disk is nothing like this. It is more like a cushion between the end plates of the vertebrae. It is round (hence the name disk) and fibrous on the outside with a soft gelatinous inside to absorb the forces to which the bones are exposed. This jelly-like inside material inside is called the nucleus pulposus, and it is this material that makes up the fibrocartilaginous embolus.

The vertebral column provides a bony protective case around the vulnerable spinal cord.

The spinal cord is the cable of nerves and nerve connections that transmits messages to and from the brain and controls the reflexes of the body. The spinal cord is fed by a network of spinal arteries.

In FCE, somehow the material from the nucleus pulposus, all the way in the center of the disk, gets into a spinal artery. The artery carries the nucleus pulposus material to the spinal cord until the artery becomes too narrow for the nucleus pulposus to go any further. The artery is plugged and the area of spinal cord it is supposed to feed dies. (The nucleus pulposis is “fibrocartilaginous” in nature, and the artery obstruction is an “embolism.”) This process is not painful except possibly briefly at first, but recovery is far from guaranteed. The good news is that after the first 24 hours, the condition is not going to get worse.

There are many theories of how disk material might gain access to the arterial blood supply, but no one really knows how this happens.

The Typical Patient

Any dog can be a victim of FCE, although about half of the victims are large-breed dogs. Some feel the Miniature Schnauzer has a higher risk for FCE as this breed tends to circulate excess blood fats and cholesterol, which may predispose to embolism.

Breeds that are called chondrodystrophic (meaning they have as part of their normal breed conformation dwarf-like characteristics) tend to calcify their disk material, making it too hard to participate in an FCE, and they are thus at lower risk. Such lower-risk breeds include Basset hounds and Dachshunds. Instead, these breeds tend to get Type I disk herniation, a different spinal problem but one at least amenable to surgery.

Most FCE dogs are young adults between the ages of 3 and 6 years. In one study, 61% were evaluated after some kind exercise injury or trauma. There may be a yelp at the time of the trauma but the injury is generally not painful. There is about a 50:50 chance that the lumbar area of the spinal cord will be affected, which means only the rear legs will be involved. Because the embolism is not generally a symmetrical event, both left and right may not be equally affected.

Will My Dog Be Okay?

This depends on how much loss of function there is. The good news, as mentioned, is that the loss of function will not progress; after the first 24 hours, the maximum function loss has occurred. Your dog may or may not be able to improve (about 74% of dogs in one study showed some improvement ultimately; other studies show at least 50% of dogs can recover fully) but be prepared for no improvement and ask yourself what kind of care will be needed and can your dog get around. Maximum improvement has generally occurred by 3 weeks after the time of the injury, with some dogs showing some additional slow improvement over months.

Many dogs are completely paralyzed. See more information on caring for a paralyzed dog.

Many dogs are simply weak in the affected limbs. They may or may not need assistance in getting around. It all depends on how severe the embolism was and where in the spinal cord it occurred.

How Can We Be Sure This Was FCE?

Acute neurologic weakness after trauma could also be caused by Type I disk herniation or by spinal cord trauma. In Type I disk herniation, a mineralized intervertebral disk “slips” upward and presses on the spinal cord. The pressure may be relieved with medication (if it is not severe) or surgery may be needed. In either case, the spot where the disk is pressing is painful, and the pain is an important distinguishing feature. Beyond this, with disk disease, abnormalities may be seen when the patient’s back is radiographed, whereas in FCE, the radiographs will appear normal.

In some cases, the collapsed disk spaces are not obvious, and more advanced spinal cord imaging is needed. A myelogram involves general anesthesia and injecting dye in the space around the spinal cord. If there is an area of compression, it will be visible, and the patient can then proceed to surgery. In FCE, there is no such compression.

As for acute spinal cord trauma, it may not be apparent whether this or FCE has occurred. If the lesion is acute, it is not unreasonable to treat it as an acute spinal injury and see if improvement results.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not yet readily available to most veterinary practices but is likely to become the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of FCE. MRI is able to distinguish embolized areas of the spinal cord from those with swelling or compression as long as at least 72 hours have elapsed from the initial event. Still, absolute confirmation of the FCE diagnosis requires a piece of spinal cord tissue for analysis, and this is not something that would be done in a living patient. For the time being, diagnosis of FCE is made based on the clinical picture of a patient in the appropriate age group with an acute spinal deficit, no other abnormalities on imaging, and no painful areas.

FCE is unlikely to be a recurrent condition, so that if a dog has one episode, they are not likely to experience another.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy for pets is an emerging field with limited availability, but it can be very helpful in maximizing mobility. This holds true for many orthopedic and spinal conditions, including FCE. Some of the exercises used to assist in rehabilitation are depicted in the pictures below.

With any pet physical rehabilitation program, a veterinarian should be on site to direct the plan of action.