Horner’s Syndrome in Cats and Dogs

A syndrome is a collection of symptoms that have significance when they go together. It is important to realize that having a syndrome is not the same as having a diagnosis. A syndrome, however, often has a limited number of causes such that recognizing a specific syndrome brings one substantially closer to a diagnosis.

What is Horner’s Syndrome?

Horner’s syndrome consists of five signs:

- Constricted pupil

- Elevated third eyelid

- Retraction of the eyeball into the head

- Slight drooping of the eyelid

- Increased pink color and warmth of the ear and nose on the affected side (very hard to detect in small animals)

These signs appear on the side of the face (and eye) with damaged sympathetic nerves.

What is the Sympathetic Nervous System?

Our bodies have numerous functions that are controlled by our nervous systems, yet we are completely unaware of them. Our heart and respiratory rates, the amount of sweat and other secretions we produce, circulation to different body areas, pupil dilation (enlargement), and constriction (shrinking) are all regulated by our nervous systems automatically and without our knowledge or control. The part of our nervous system dedicated to these automatic systems is called the autonomic nervous system.

Sympathetic vs Parasympathetic

The autonomic nervous system is divided into the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. The parasympathetic system maintains a status quo, a normal business-as-usual state; the sympathetic system prepares the body for a fight-or-flight situation.

For example, the sympathetic nervous system kicks in with anxiety or fear leading to increased sweating, pupil dilation, increased heart and respiration rates, and increased blood flow to the muscles. The body is preparing to defend its life either by running or fighting. When danger passes, the parasympathetic nervous system kicks in to return everything to normal. Both systems coexist to provide balance in a healthy body.

In the eye, the sympathetic nerve fibers dilate the pupil, widen the eyelids, drop the third eyelid, and keep the eye in a forward position in the socket. The parasympathetic nerves constrict the pupil, raise the third eyelid, and retract the eye for protection. Both systems are working at the same time, one system slightly dominating the other depending on what is happening.

When the sympathetic nerves controlling one of the eyes are damaged, only the parasympathetic nerves work and Horner’s syndrome is created.

How can the Sympathetic Damage Occur?

The nerve carrying the tiny nerve fibers that provide sympathetic control to the eye has a long path, and damage may occur anywhere along it. Also, some types of injuries are more likely to occur in certain areas along the path.

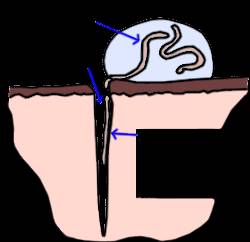

This path begins in the brain’s hypothalamus. A group of nerves exit the hypothalamus and travel down the brainstem, continuing down the spinal cord, down the length of the neck, and just into the chest. This segment is called the central segment and is shown in blue in the illustration to the right. This pathway extends from the brain and brain stem down to the level of the second thoracic vertebra, all within the spinal cord.

From here, the nerves form right and left bundles and exit the spinal cord to make a U-Turn and travel back towards the eyes. The bundles are called the right and left sympathetic trunks (or the “pre-ganglionic segments”) and they extend from the top of the chest back to the area of the middle ear. They are shown in red in the illustration.

From there, the nerves connect to the last segment of nerves (the postganglionic segments – one on the right and one on the left), as shown in yellow. This segment starts just below the ear and travels to the eye.

The damage can occur in the neck or spinal cord area, the ear area, or the eye area. Damage can occur in the form of trauma, tumor involvement, infarction (abnormal blood clot), middle ear infection, or diseases of the eye itself. Each segment of the nerve pathway is vulnerable to different types of damage, so knowing which segment is involved gives us a good idea of what caused the damage.

Locating the Damage

As mentioned, localizing which area of the sympathetic nervous system is affected goes a long way in determining the nature of the damage, as different areas of the system are prone to different types of injury. Eye drops can be used to stimulate different areas of the above pathway and determine which area is damaged. Damage is described as being first order, second order, or third order. Most lesions turn out to be third order.

First Order Lesions (involving the blue segment)

Diseases that hit nerve fibers in the brain, brainstem, or spinal cord include tumors of the brain, vascular accidents (such as stroke) in the nerve tissue, fibrocartilaginous embolism in the spinal cord where disk material sprays into the spinal cord, or even a herniated intervertebral disk in the area of the neck. Horner’s syndrome stemming from any injury such as one of these might prompt a search for other neurologic issues. Advanced imaging such as an MRI might be a good idea.

Second Order Lesions (involving the preganglionic red segment)

Diseases that strike the sympathetic trunk include foreleg injuries especially if the foreleg is pulled and the nerves that exit the spinal cord in the armpit area become over-stretched. Sometimes a mass in the chest, such as a tumor or fungal granuloma, will damage the sympathetic trunk. Neck trauma such as pulling very hard on a leash could be severe enough to cause a second order lesion. If there is no obvious history to suggest injury, it might be a good idea to radiograph the chest to see if there are masses in the lung that might be involved in a second order lesion.

Third Order Lesions (involving the postganglionic yellow segment)

These are the most common causes of Horner’s syndrome because ear infections are so common for small animals. Inflammation in the middle ear can easily lead to Horner’s syndrome. Third order lesions are associated with vestibular disease, the imbalance and dizziness of the middle ear infection, in many cases. When Horner’s syndrome localizes as third order, the ears should be thoroughly investigated as the source.

Treatment

It is not necessary to treat Horner’s syndrome. The syndrome is not painful and does not interfere with vision. The significance of the syndrome is that it indicates nerve damage that must be recognized. If you wish to treat the syndrome for cosmetic reasons, phenylephrine eye drops can be prescribed to relieve clinical signs. The most important thing is to determine what caused the Horner’s syndrome. Horner’s syndrome itself probably does not need treatment, but its underlying cause very well might.